Coastal Impoundment Vulnerability and Resilience Project

The Coastal Impoundment Vulnerability and Resilience Project (CIVRP), funded by the Department of the Interior via the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, aims to map and catalog all state, federal, and privately owned coastal impoundments from Virginia to Maine. In addition, we are compiling information on the ecological and societal services provided by these sites and assessing their vulnerability to sea level rise. We will develop a ranking of impoundments based on metrics related to their ecological value, importance to human populations, and potential for maintaining their structural integrity. The project is a cooperative effort of a diverse team of partners including researchers from New Jersey Audubon, National Wildlife Federation, Conservation Management Institute (Virginia Tech), Princeton Hydro, and the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Impoundment Map

Impoundment Sites

Site Description

State: Delaware

County: Sussex

Ownership: State

Impoundments

35 Acre Pond: 53 acres

65 Acre Pond: 76 acres

Goose Pond: 73 acres

Muddy Creek: 33 acres

Mulberry Pond: 80 acres

Zigzag Marsh: 27 acres

Ecology and Management

Assawoman Wildlife Area in Bethany Beach, DE contains six impoundments covering over 300 acres. The impoundments host robust numbers of waterfowl including Wigeon, Gadwall, Buffleheads and Snow Geese during the winter. The Delaware Division of Fish and Wildlife does mid-winter waterfowl flights and has a Christmas Bird Count.

The impoundments are all managed to provide habitat for wintering and migratory waterfowl, but with management regimes specific to each impoundment. Water levels are kept relatively stable to promote wigeongrass production in the 65-Acre, 35-Acre, Mulberry, and Zigzag Marsh Ponds.

Vulnerability

The impoundments border the little Assawoman Bay, one of Delaware’s inland bays, and are thus subject to wave energy and tidal forces. The impoundments have experienced some overtopping and saltwater intrusion during hurricanes, including Hurricane Sandy.

Human Value

There are no visitor use surveys at Assawoman WMA, but the site does host campers from Camp Barnes, a Delaware State Police sponsored free summer camp for kids between 10 – 13 years of age.

Literature Resources

Below is a list of articles describing research occurring at or near the impoundments:

Chamberlain, E. B. A survey of the marshes of Delaware. Dover, Delaware: The State of Delaware, Board of Game and Fish Commissioners; 1951.

Chan, S., and S. Shulte. A Plan for Monitoring Shorebirds During the Non-breeding Season in Bird Monitoring Region Delaware – BCR 30. Manomet, Massachusetts: Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences; 2003.

Coxe, R. Historical analysis and map of vegetation communities, land covers, and habitats of Assawoman Wildlife Area, Sussex County, Delaware. Smyrna, Delaware: Delaware Division of Fish and Wildlife, Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program; 2012. 289 p.

Florschutz, O. Mosquito production and wildlife usage in natural, ditched, and impounded tidal marshes on Assawoman Wildlife Area, Delaware. University of Delaware; 1959.

Gano Jr., R. D. Assawoman Wildlife Area Management Plan. Dover, Delaware: Delaware Division of Fish and Wildlife; 1996.

Gano Jr., R. D. 1991. Assawoman Wildlife Area: a description of its history and present use. Pages 27-28 In Ullman, W., editor. A day in the life of Delaware’s forgotten bay: a scientific survey of Little Assawoman Bay, Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control, Dover, Delaware.

Site Description

State: Virginia

County: Virginia Beach

Ownership: Federal

Impoundments

A-pool: 181 acres

B-pool: 127 acres

C-pool: 178 acres

D-pool North: 2 acres

D-pool South: 9 acres

E-pool: 14 acres

G-pool: 78 acres

H-pool: 50 acres

J-pool: 89 acres

C-storage pool: 49 acres

B-storage pool: 13 acres

False Cape East: 92 acres

False Cape West: 94 acres

Frank Carter group: 25 acres

Ecology and Management

Back Bay NWR was established in 1938, and like many Refuges its primary management goal is focused on migratory and wintering waterfowl and shorebirds. The Refuge works to provide quality habitat that maintains or increases existing levels of migratory waterfowl and shorebird use. Sixteen impoundments occur on the refuge including five in the separate “Frank Carter” group. Two additional impoundments occur on the adjacent False Cape State Park, but are managed by Back Bay NWR staff. The impoundments are oligohaline (almost fresh water) and most are surrounded by a network of dirt roads atop their dikes.

Sixteen impoundments occur on the Refuge and provide quality habitat that maintains or increases existing levels of migratory waterfowl and shorebird use.

These management impoundments at Back Bay support a broad array of bird species. Specifically, the impoundments provide habitat for over 30 waterfowl species. Wading bird populations vary with the season. Most species are present only during their migrations and throughout the summer. Impoundment water levels are drawn down during July to provide additional fish and amphibian forage for these birds, particularly young of the year, prior to their migrations. Refuge shorebirds include the sandpipers, plovers, dunlins, knots, yellowlegs, dowitchers, and sanderlings, among others. They utilize the wet mud/sand flats and beach tidal habitats, where they search for the high-protein invertebrate foods they need to sustain them during their exhausting migrations. They use the Back Bay Refuge beach and impoundments vicinities most during their spring and fall migrations. The Refuge draws down the water levels of its 1000-acre impoundment complex to provide them with additional feeding areas during those periods. The secretive group of saltmarsh birds present on the impoundments includes the rails, gallinules, moorhens and coots, among others. King rail and American coot are most commonly heard or seen on bird surveys.

The habitats provided by the impoundments also support many other species, including a diverse and healthy fish community; river otters; and two state rare beetles and two rare moths. The impoundments at Back Bay NWR also support federal threatened (FT) and endangered (FE) species. These include the piping plover (FT), Kemps ridley (FE), loggerhead sea turtle (FT), green sea turtle (FT), leatherback sea turtle (FE), and seabeach amaranth (FT). However, in terms of sea turtles, those that nest here are the loggerheads. Several Kemp’s ridley have been seen since 2012, and occasionally there are green sea turtle. The state endangered eastern big-eared bat is suspected to use Back Bay NWR, but its occurrence has not been confirmed. The State threatened glass lizard was documented on Back Bay NWR during the late 1990s, and the most recent siting was in 2010. The state endangered Eastern tiger salamander is also present on the Refuge.

Several non-native and or invasive species threaten management of the impoundments. The feral hog, feral horse, nutria and resident Canada goose all consume moist soil vegetation that is grown each year in the impoundment complex to feed wintering and migrating waterfowl. If too much browsing on this important resource is allowed to occur, the ability of the Refuge to provide wintering waterfowl foods will be severely reduced. Feral hogs also significantly impact dike slopes and public use areas with their rooting behavior as they seek tubers and other foods below the surface of the ground. Such turned-over ground contributes to soil erosion around dike slopes, and creates a public safety hazard, while also removing the food-plants/vegetative cover.

In terms of management, water levels in the impoundments are drawn down during the spring and early fall months to create shallow mud flats for the shorebird migration. This is during months of late April – May and late August – September. During the summer (July, August) pools are managed for wading/marsh birds are emergent marsh with shallow water and patches of emergent plants.

Vulnerability

The Refuge has over 8 miles of dike roads, which form 18 wetland impoundments managed by over 25 water control structures and two pump stations. Two additional impoundments (managed by the refuge) occur in the adjacent False Cape State Park. The impoundments, however, are relatively protected by the Refuge’s barrier dune system.

Human Value

The Refuge sees approximately 100,000 to 120,000 visitors per year. The Refuge also provides some education opportunities. The trail system around the Refuge headquarters; an outdoor classroom; pond activity pier; and the oceanfront, bay, and impoundment areas all serve as environmental education resources for individuals and groups. A number of self-guided interpretive kiosks and panels are strategically located throughout the Refuge, with the highest concentration in the Refuge headquarters area.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Geralyn Mireles, USFWS Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge, for providing helpful information used on this page.

Literature Resources

Below is a list of articles describing research occurring at or near the impoundments:

Anderson, J. T. 2006. Evaluating competing models for predicting seed mass of Walter’s millet. Wildlife Society Bulletin 34:156-158.

Brandwein, J. Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan. Washington, D. C.: U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service; 2010.

Brinkley, E. S., and J. B. Patteson. 2001. Yellow-legged gull (Larus cachinnans cf. michahellis) at Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Virginia Beach. Raven 72:66-75.

Green, A., J. Lyons, M. Runge, W. Kendall, H. Laskowski, S. Lor, and S. Guiteras. Timing of impoundment drawdowns and impact on waterbird, invertebrate, and vegetation communities within managed wetlands, Study manual – Final version field season 2007. Laurel, Maryland: USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center; 2007.

Green, A. W., W. L. Kendall, H. P. Laskowski, J. E. Lyons, L. Socheata, and M. C. Runge. Draft version of the USFWS R3/R5 Regional Impoundment Study. Washington, D. C.: U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service; 2008.

IWMM [Integrated Waterbird Management and Monitoring Project]. Project Update – October 2010. http://iwmmprogram.ning.com/: Integrated Waterbird Management and Monitoring Project; 2010.

McLeod, G. M., J. Daigneau, and R. J. Gucwa. 2005. Supervised classification of landsat-7 imagery for the detection of Phragmites australis in Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge. Journal of the North Carolina Academy of Science 121:61-70.

Pease, M. L., R. K. Rose, and M. J. Butler. 2005. Effects of human disturbances on the behavior of wintering ducks. Wildlife Society Bulletin 33:103-112.

Rogers, S. L., J. A. Collazo, and C. A. Drew. 2013. King Rail (Rallus elegans) occupancy and abundance in fire managed coastal marshes in North Carolina and Virginia. Waterbirds 36:179-188.

Schulte, S., and S. Chan. A Plan for Monitoring Shorebirds During the Non-breeding Season in Bird Monitoring Region Virginia – BCR 30 and 27.

Manomet, Massachusetts: Manomet Center for Conservation Science; 2008.

Sherfy, M. H. Nutritional value and management of waterfowl and shorebird foods in Atlantic coastal moist-soil impoundments. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University; 1999.

Sherfy, M. H., and R. L. Kirkpatrick. 1999. Additional regression equations for predicting seed yield of moist-soil plants. Wetlands 19:709-714.

Stone, L. F. Practicing conservation biology at Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge. Ohio: Miami University; 2014.

Weldon, A. Important bird areas (IBAs) in the commonwealth of Virginia. Virginia: National Audubon Society; 2007.

Site Description

State: Maryland

County: Dorchester

Ownership: Federal

Impoundments

13 impoundments: 351 total acres

Ecology and Management

Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge has the largest breeding population of American Bald Eagles north of Florida. Photo by Alan Cressler.

The thirteen impoundments within the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge are renowned for their abundance and diversity of waterfowl and wading bird species. Additionally, Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge is home to the largest breeding population of American Bald Eagles north of Florida and has been named a Wetland of International Importance. Observations by refuge staff and ornithologists have identified 281 bird species that regularly use the entire refuge complex. Along Wildlife Drive, which forms the bayside barrier for many of the impoundments, 242 bird species have been reported to eBird.org, including impressive high counts of and waterfowl. For example, highs of 15,000 Canada Geese; 12,000 Snow Geese; 1,150 Tundra Swans and 692 Common Merganser were seen from Wildlife Drive since 2010. The Friends of Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge report that upwards of 35,000 geese and 15,000 ducks can be seen during the November migration. Waterbird use of the impoundments is monitored through the Integrated Waterbird Management and Monitoring Program (IWMM).

The impoundments are subject to moist soil management. Pool drawdowns typically occur between mid-March and early June, depending on the wildlife objectives and moist soil plant/invertebrate response desired. Drawdown is initiated in most pools first by gravity flow, but pumping is often required in most of the impoundments to remove all the water. Several permanent and seasonal pumping stations, utilizing gasoline, diesel, and electric pumps, are operated and maintained. Rates of drawdown are critical, and, depending on the pool bottom topography and soil type or organic content, can occur rapidly or must be prolonged. All drawdowns are completed by mid-June, and pool bottoms are maintained as moist as weather conditions will allow to facilitate the germination, growth, and production of a wide diversity of emergent moist soil plants.

Vulnerability

The impoundments at Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge are sheltered by around 9,000 acres of brackish marsh. However, between 1938 and 2006 marsh was lost at a rate of 74 acres per year (Lerner et al. 2013). As this rate increases with the rate of sea-level rise over the next century the habitat within the impoundments will become increasingly valuable to birds which use the refuge. Despite their proximity to open water, the impoundments have not historical records of damage.

Human Value

Blackwater NWR received 82,163 visitors in 2011. The refuge also hosts a Youth Conservation Corps program in the summer, as well as providing educational opportunities to 1,700 students and scouts on an annual basis. Despite its rural location Blackwater NWR is one of the most popular birding locations in the state of Maryland.

Literature Resources

Below is a list of articles describing research occurring at or near the impoundments:

Beyer, W. N., D. Day, A. Morton, and Y. Pachepsky. 1998. Relation of lead exposure to sediment ingestion in mute swans on the Chesapeake Bay, USA. Environmental toxicology and chemistry 17:2298-2301.

Carowan, G. A. Chesapeake Marshlands National Wildlife Refuge Complex Comprehensive Conservation Plan. Washington, D. C.: U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service; 2006.

Green, A., J. Lyons, M. Runge, W. Kendall, H. Laskowski, S. Lor, and S. Guiteras. Timing of impoundment drawdowns and impact on waterbird, invertebrate, and vegetation communities within managed wetlands, Study manual – Final version field season 2007. Laurel, Maryland: USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center; 2007.

Green, A. W., W. L. Kendall, H. P. Laskowski, J. E. Lyons, L. Socheata, and M. C. Runge. Draft version of the USFWS R3/R5 Regional Impoundment Study. Washington, D. C.: U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service; 2008.

Jensen, M. N. 2003. Coming of age at 100: Renewing the National Wildlife Refuge System. Bioscience 53:321-327.

Larsen, C., I. Clark, G. Guntenspergen, D. Cahoon, V. Caruso, C. Hupp, and T. Yanosky. The Blackwater NWR Inundation Model: Rising Sea Level on a Low-lying Coast—Land Use Planning for Wetlands. Reston, Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey; 2004. Report nr 04–1302.

Site Description

State: Delaware

County: Kent

Ownership: Federal

Impoundments

Bear Swamp Pool: 226 acres

Finis Pool: 121 acres

Raymond Pool: 95 acres

Shearness Pool: 458 acres

Ecology and Management

Great Egret, Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge, Delaware. Photo credit: Mike Carlo/USFWS

The impoundments at Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge are nationally known birding hotspots, especially for shorebirds, waterfowl, and wading birds. Bombay Hook NWR has been designated a Ramsar Wetland of International Importance as well as a Globally Important Bird Area. U.S. Fish and Wildlife lists 278 birds that use the wider refuge and eBird reports counts of 239 species at Raymond Pool, 219 species at Shearness Pool, 226 species at Bear Swamp, and 178 species at Finis Pool. Raymond Pool hosts especially impressive numbers of shorebirds and waterfowl with high counts of 10,100 Dunlin; 7,000 Semipalmated Sandpiper; nad 4,890 Short-billed Dowitcher.

The impoundments at Bombay Hook NWR are managed under a moist soil management regime with water levels are drawn down in the spring to provide mudflats for migrating shorebirds. This permits the germination and growth of lush vegetation, and wading birds feed on fish in the pools that form. The impoundments are then flooded in the fall to give dabbling ducks access to the seeds of the wetland plants. In the spring the cycle begins again. Invasive Common Reed (Phragmites australis) has been an ongoing challenge in maintaining the productivity of the impoundments.

Vulnerability

Most of the impoundments at Bombay Hook NWR are sheltered by vegetated marsh but still experience occasional overtopping. Shearness Pool is exposed to higher wave energy due to the fact that it borders a large unvegetated intertidal flat. While Bombay Hook has not experienced any failures of their imoundments they are subject to occasional overwash and occasional cave-ins due to localized muskrat activity.

Human Value

Bombay Hook NWR receives approximately 110,000 visitors every year and is the most popular birding site in the State of Delaware. Bombay Hook staff, lead a variety of environmental education and interpretation programs each year for local schools and collaborate on research with the University of Delaware and Delaware State University.

Literature Resources

Below is a list of articles describing research occurring at or near the impoundments:

Anderson, J. T. 2006. Evaluating competing models for predicting seed mass of Walter’s millet. Wildlife Society Bulletin 34:156-158.

Breese, G., K. Kalasz, J. Lyons, C. Boal, J. Clark, M. DiBona, R. Hossler, B. Jones, B. Meadows, M. Stroeh, B. Wilson, and M. Runge. Structured decision making for coastal managed wetlands in Delaware. Shepherdstown, West Virginia: United States Fish and Wildlife Service, National Conservation Training Center; 2010.

Chamberlain, E. B. A survey of the marshes of Delaware. Dover, Delaware: The State of Delaware, Board of Game and Fish Commissioners; 1951.

Chan, S., and S. Shulte. A Plan for Monitoring Shorebirds During the Non-breeding Season in Bird Monitoring Region Delaware – BCR 30. Manomet, Massachusetts: Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences; 2003.

Conroy, M. J., G. R. Costanzo, and D. B. Stotts. 1989. Winter survival of female American black ducks on the Atlantic coast. The Journal of Wildlife Management 53:99-109.

Detterline, J., and W. Wilhelm. 1991. Survey of pathogenic Naegleria fowleri and thermotolerant amebas in federal recreational waters. Transactions of the American Microscopical Society 110:244-261.

Erwin, R. M., D. K. Dawson, D. B. Stotts, L. S. McAllister, and P. H. Geissler. 1991. Open marsh water management in the mid-Atlantic region: aerial surveys of waterbird use. Wetlands 11:209-228.

Green, A., J. Lyons, M. Runge, W. Kendall, H. Laskowski, S. Lor, and S. Guiteras. Timing of impoundment drawdowns and impact on waterbird, invertebrate, and vegetation communities within managed wetlands, Study manual – Final version field season 2007. Laurel, Maryland: USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center; 2007.

Green, A. W., W. L. Kendall, H. P. Laskowski, J. E. Lyons, L. Socheata, and M. C. Runge. Draft version of the USFWS R3/R5 Regional Impoundment Study. Washington, D. C.: U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service; 2008.

Griffith, R. 1946. Nesting of Gadwall and Shoveller on the Middle Atlantic Coast. The Auk 63:436-438.

Harding, J. J. 1980. Birding the Delaware Valley Region: A Comprehensive Guide to Birdwatching in Southeastern Pennsylvania, Central and Southern New Jersey, and Northcentral Delaware. Temple University Press, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Hill, M. R., and R. B. Frederick. 1997. Winter movements and habitat use by greater snow geese. The Journal of Wildlife Management 61:1213-1221.

IWMM [Integrated Waterbird Management and Monitoring Project]. Project Update – October 2010. http://iwmmprogram.ning.com/: Integrated Waterbird Management and Monitoring Project; 2010.

Lunt, D. C. 1986. Taylors Gut: In the Delaware State. Middle Atlantic Press, Wilmington, Delaware.

Mather, T. Nitrogen and phosphorous analysis of Raymond and Shearness impoundments, Bombay Hook NWR, Summer 1979.

Unpubl. Report. Newark, Delaware: Dept.of Entomology and Applied Ecology, Univ.of Delaware; 1979.

Mathis, W. N., and T. Zatwarnicki. 2010. New Species and Taxonomic Clarifications for Shore Flies from the Delmarva States (Diptera: Ephydridae). Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 112:97-128.

Anonymous. Effects of open marsh water management (OMWM) on bird populations of a Delaware tidal marsh, and OMWM’s use in waterbird habitat restoration and enhancement. Waterfowl and wetlands symposium: proceedings of a symposium on waterfowl and wetlands management in the coastal zone of the Atlantic Flyway. Delaware Coastal Management Program, Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control, Dover, DE; 1987. 298 p.

Murphey, F. J., and P. P. Burbutis. 1967. Straw Infusion Attractiveness to Gravid Female Culex salinarius. Journal of Economic Entomology 60:156-161.

Murray, M. 2014. Delaware gets millions to help beaches, wetlands. Delaware Online June 8, 2014:1.

Murray, M., and J. Montgomery. 2012. Marsh impoundments create questions on future responses by state officials. Delaware Online October 23, 2012:1.

Philipp, K. R. 2005. History of Delaware and New Jersey salt marsh restoration sites. Ecological Engineering 25:214-230.

Pinkney, A. E., P. C. McGowan, D. R. Murphy, T. P. Lowe, D. W. Sparling, and L. C. Ferrington. 2000. Effects of the mosquito larvicides temephos and methoprene on insect populations in experimental ponds. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 19:678-684.

Wayne, W. J., and T. E. Roberts. 1972. The Summer Scene. The Delmarva Ornithologist 7:4-6.

Wilson, B., D. Siok, C. Pinkerton, K. Smith, and B. Scarborough. Evaluating the Evolution of Natural Tidal and Managed Wetlands in Delaware. A presentation given at DE Wetlands Conference. Dover, Delaware: Delaware National Estuarine Research Reserve; 2012.

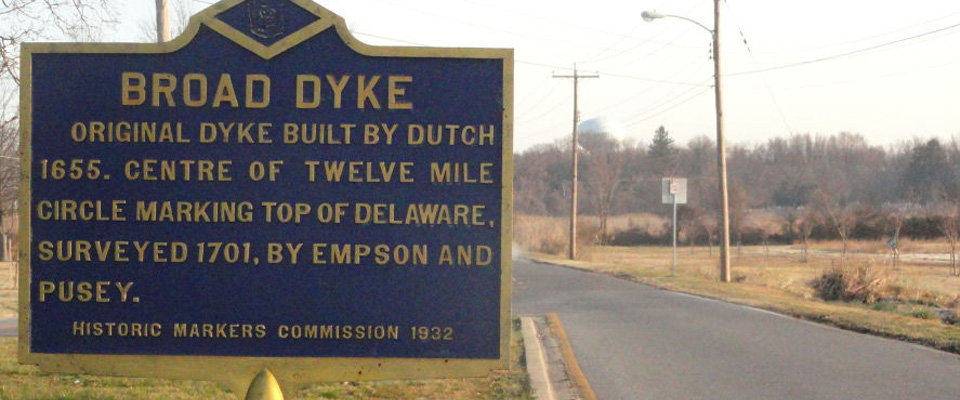

Site Description

State: Delaware

County: New Castle

Ownership: Private

Impoundments

Broad Dyke Marsh: 136 acres

Ecology and Management

Broad Dyke Marsh is located just north of New Castle, DE. It is a fairly small impoundment at only 55 acres, but is unique in the fact that the original dikes date back to the 1655 and were constructed by Dutch settlers, making it likely one of the oldest impoundments in the country. There is no data available on the bird species which use the dyke, but there have been extensive vegetation surveys and the site that has shown that treatment and improved management of the water level has improved native vegetation diversity and drastically reduced invasive phragmites. The site is owned by the Trustees of New Castle Commons, a local non-profit group.

Vulnerability

The impoundment is vulnerable to coastal storms and sea-level rise and experience damage during Sandy. The impoundment is a critical buffer for the town of Historic New Castle by absorbing the influx of water during these severe coastal storms and failure of the dike would be catastrophic to low-lying areas of the town.

Human Value

There is no human use data for this site, but it is located near Historic New Castle, a popular tourist destination in Delaware as well as along the East Coast Greenway bicycle trail. There are no known educational or outreach activities at Broad Dyke Marsh.

Literature Resources

Below is a list of articles describing research occurring at or near the impoundments:

Catts, W. P., and T. Mancl. “To keep the banks, dams and sluices in repair”: an historical context for Delaware River dikes, New Castle County, Delaware. Dover, Delaware: Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control; 2013.

DDNREC [Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control]. Northern Delaware Wetland Rehabilitation Program. Dover, Delaware: Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control; 2001.

Greenstone Engineering, I. Broad Marsh Dike Operation and Maintenance Manual. Wilmington, Delaware: Greenstone Engineering, Inc.; 2011.

Kalasz, K., C. Boal, G. Breese, J. Clark, M. DiBona, R. Hossler, B. Jones, J. Lyons, R. E. Meadows, M. Stroeh, and B. Wilson. The importance of impoundments to wildlife: managing now and into the future. A presentation given at the Delaware Wetlands Conference. Dover, Delaware: Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control; 2012.

Meredith, W. H., T. J. Moran, and R. E. Meadows. Managing Delaware’s Coastal Wetlands for Biodiversity. Dover, Delaware: Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control; 2002.

Site Description

State: Delaware

County: Sussex

Ownership: State

Impoundments

Gordon’s Pond: 317 acres

Ecology and Management

.

Gordon’s Pond is a saltwater impoundment located in Cape Henlopen State Park.

Gordon’s Pond is a saltwater impoundment located in Cape Henlopen State Park along the Atlantic coast of Delaware. It is thought to have originated centuries ago as a result of salt harvesting activities (Forney 2014). Currently, the impoundment is managed both for mosquito control and to provide habitat for migratory shorebirds and waterfowl. According to eBird, 232 species have been observed at this site. The water levels are managed by the Delaware State Parks system and generally allowed to fill during winter and is drawn down in the summer. Inputs come from both rain water as well as from the Lewes-Rehoboth Canal.

Vulnerability

“These days, it’s only a rare and powerful nor’easter that breaks through the dunes every 10 years or so to push ocean water into Gordons Pond.”

– (Forney 2014)

Gordon’s Pond is impounded to the east by a natural dune system, which experiences breaches on average once every 10 years during coastal storms. Despite these breaches the dunes which impound Gordon’s pond are healthy and not predicted to be especially vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

Human Value

Being situated directly adjacent to the Delaware beaches and between the popular towns of Lewes and Rehoboth Beach, Gordon’s Pond receives large numbers of visitors in the summer months.

Literature Resources

Below is a list of articles describing research occurring at or near the impoundments:

Forney, D. 2014. Gordons Pond water levels and our salt-gathering past. Cape Gazette June 20, 2014:1.

GPWG [Gordons Pond Working Group]. Preliminary assessment of trail alternatives. Dover, Delaware: Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control; 2010.

Manomet [Manomet Center for Conservation Science]. 2015. ISS/PRISM Tools: Site Map, Site List and Site Reports. 2015:1.

Site Description

State: Virginia

County: Accomack

Ownership: Federal

Impoundments

Black Duck Pool (A pool)

Farm Fields Pool

Gadwall Pool (E pool)

Mallard Pool (C pool)

North Wash Flats

Old Fields

Pintail Pool (D pool)

Ragged Point

Shoveler Pool (B-North pool)

Snow Goose Pool (B-South pool)

South Wash Flats

Sow Pond

Swan Cove Pool (F-Pool)

Total: 2353 acres

Ecology and Management

Birds feeding off Swan’s Cove Trail at Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge. Credit: Emma Kerr/USFWS

Most of the impoundments at Chincoteague NWR were constructed in the 1950s and 1960’s to provide migratory bird protection, with the primary purpose of providing waterfowl migration and wintering habitat. When first established the Refuge focused more on single species management. Today, however, the Refuge manages impoundments for a suite of wildlife throughout the year. The impoundments also supply numerous habitat benefits, including wintering/migratory habitat for waterfowl; fresh/brackish vegetation roots and seed as food for wintering waterfowl; food sources for waterbirds of conservation concern such as snowy egret, glossy ibis, Forster’s and gull-billed terns; and shorebird migratory stopover habitat for many species of conservation concern, including short-billed dowitcher, dunlin, and semipalmated sandpiper. The Refuge also manages habitat for American black ducks, as part of a long-term effort, in compliance with the North American Waterfowl Management Plan. The impoundments are also managed for a range of aquatic species and other species of conservation concern. Several federal and state endangered and threatened species are also found within the Refuge. They include: piping plover (FT), red knot (FT), roseate tern (FE), Delmarva fox squirrel, Northern long-eared bat (FT), gull-billed tern (ST), Wilson’s plover (SE), and peregrine falcon (ST).

To support the wide array of bird species found at the Refuge, impoundment water levels are closely managed to provide adequate food, in the form of vegetation (seed or roots) and/or aquatic invertebrates, fresh water, and loafing areas. However, all Refuge impoundment management strategies depend entirely on precipitation as their sole source of freshwater for the generation of fresh/brackish water plants, and gravity or evaporation for drawdown. Both mechanisms limit management capabilities. Tidal cycles and strong coastal storm events, especially nor’easters and hurricanes, further challenge the attainment of management goals for impoundments. Non-native Phragmites also poses a management challenge.

Vulnerability

Chincoteague’s impoundments are located between mean high and spring high tide and abut upland areas as well as fresh or brackish marshes not affected by tides. Because the impoundments generally are located above the high tide level, estuarine water cannot enter them. However, tidal influx can occur through the Virginia Creek water control structure (WCS) into Old Fields Impoundment. During severe weather and extreme high tides, overwash reaches impoundments from the sea and Bay side; Black Duck (A) Pool, Snow Goose (B-South) Pool, Shoveler (B-North) Pool, Mallard (C) Pool, Pintail (D) Pool, Swan Cove (F) Pool, Wash Flats, and Old Fields impoundments are most susceptible. As noted previously, because the impoundments depend on precipitation for freshwater inputs, tidal cycles and strong coastal storm events, especially nor’easters and hurricanes, challenge the attainment of management goals for impoundments. Additionally, as sea level continues to rise and more frequent overwash events occur, the Refuge expects damage to dikes and other impoundment infrastructure. Maintaining water depths at desirable levels may also become more difficult.

Human Value

Chincoteague NWR provides significant recreation and education opportunities for visitors. Specifically, the impoundments concentrate large flocks of birds, providing wildlife viewing, and opportunities for photography, education, and interpretation. In 2010, approximately 1.4 million people visited the Refuge. In terms of education, the Refuge offers a wide range of programming, including day camps to family programs, and undergraduate and graduate research opportunities. The Refuge also works with local K to 12 schools, communities, and educational organizations to provide classroom and hands-on programs both on and off the refuge for youth. Teacher workshops and Teacher Guided Learning Opportunities are also available.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Kevin Holcomb, USFWS Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge, for providing helpful information used on this page.

Literature Resources

Below is a list of articles describing research occurring at or near the impoundments:

Carson, Rachel. Chincoteague: A National Wildlife Refuge. Washington, D. C.: U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service; 1947.

Conroy, M. J., G. R. Costanzo, and D. B. Stotts. 1989. Winter survival of female American black ducks on the Atlantic coast. The Journal of Wildlife Management 53:99-109.

Green, A., J. Lyons, M. Runge, W. Kendall, H. Laskowski, S. Lor, and S. Guiteras. Timing of impoundment drawdowns and impact on waterbird, invertebrate, and vegetation communities within managed wetlands, Study manual – Final version field season 2007. Laurel, Maryland: USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center; 2007.

Green, A. W., W. L. Kendall, H. P. Laskowski, J. E. Lyons, L. Socheata, and M. C. Runge. Draft version of the USFWS R3/R5 Regional Impoundment Study. Washington, D. C.: U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service; 2008.

Hinke-Sacilotto, I. 2005. Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge: An Ecological Treasure. Big Earth Publishing, Boulder, Colorado.

IWMM [Integrated Waterbird Management and Monitoring Project]. Project Update – October 2010. http://iwmmprogram.ning.com/: Integrated Waterbird Management and Monitoring Project; 2010.

Morton, J. M., R. L. Kirkpatrick, and M. R. Vaughan. 1990. Changes in body composition of American black ducks wintering at Chincoteague, Virginia. Condor 92:598-605.

Schulte, S., and S. Chan. A Plan for Monitoring Shorebirds During the Non-breeding Season in Bird Monitoring Region Virginia – BCR 30 and 27.

Manomet, Massachusetts: Manomet Center for Conservation Science; 2008.

USFWS [United States Fish and Wildlife Service]. Chincoteague and Wallops Island National Wildlife Refuges Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Environmental Impact Statement. Hadley, Massachusetts: U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service; 2006.

Site Description

State: Maryland

County: Somerset

Ownership: State

Impoundments

Deal Island Impoundment: 2659 acres

Ecology and Management

Increasing submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) is one of the management goals for the Dear Island impoundment.

Deal Island Wildlife Management Area (13,000 acres) includes a single large impoundment (> 2500 acres) along the lower Chesapeake Bay in Somerset County, Maryland. Deal Island WMA is part of the larger Somerset-Wicomico Marshes Important Birding Area (IBA) as identified by the National Audubon Society. According to eBird, 207 bird species have been identified within the Deal Island impoundment. Among them, two Highest Priority species for Bird Conservation Region (BCR) 30, American Black Duck and Saltmarsh Sharp-tailed Sparrow, are abundant at Deal Island. Additional Priority NAWCA (North American Wetland Conservation Act) Species including: Pied-billed Grebe, Horned Grebe, American Bittern, Least Bittern, Snowy Egret, Bald Eagle, Solitary Sandpiper, Lesser Yellowlegs, Semipalmated Sandpiper, Short-billed Dowitcher, Least Tern, Short-eared Owl, and Seaside Sparrow also use the impoundment.

The original tidal marsh at Deal Island WMA was impounded in the 1960s. Between its creation and the 1990s, the impoundment was important habitat for waterfowl and wading birds. Peak numbers of waterfowl sometimes exceeded 20,000 birds. However in the mid-1990s the number and diversity of birds began to decline and submerged aquatic vegetation was much less abundant. This trend continued until 2009 when a new management regime, based around increasing the amount of SAV was implemented. The water control structures were improved. Water levels are managed to promote SAV growth. In addition, hunting days have been limited and gas motors are prohibited to reduce disturbance and prevent damage to existing SAV beds. As a result of these changes the impoundment has seen a rebound in both SAV and waterfowl.

Vulnerability

The impoundment at Deal Island is highly vulnerable to sea-level rise and already experiences nearly weekly overtopping at the emergency spillway. In addition muskrat burrows also cause small leaks through the berm and there is some berm erosion during storm events. Despite being only 2 feet above mean high tide there have been no large scale failures in the past.

Human Value

There are no visitor use studies, but staff estimate that over 100 people visit the impoundment each week for hunting, crabbing or bird watching. Deal Island WMA also cooperates with the nearby Chesapeake Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve for research on SAV and the area is used by local grade schools and colleges for educational field trips. The impoundment also buffers State Route 326, the only road connection to the rural fishing community of Deal Island, from wave energy to the south.

Literature Resources

Below is a list of articles describing research occurring at or near the impoundments:

Carroll, L., K. Keller, C. Ervin, and P. Delgado. Baseline Characterization of a Deteriorating Wetland Community in the Deal Island Impoundment, Lower Eastern Shore, Maryland (Poster). Maryland: Chesapeake Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve; 2009.

Ducks Unlimited. Wetlands Enhanced on Deal Island Wildlife Management Area. 2015:1.

Erwin, R. M., D. K. Dawson, D. B. Stotts, L. S. McAllister, and P. H. Geissler. 1991. Open marsh water management in the mid-Atlantic region: aerial surveys of waterbird use. Wetlands 11:209-228.

MDNR [Maryland Department of Natural Resources]. Monitoring the Deal Island Impoundment at Monie Bay. 2015:1.

MDNR [Maryland Department of Natural Resources]. Deal Island WMA. http://dnr.maryland.gov/wildlife/publiclands/eastern/dealisland.asp 2015:1.

Walbeck, D. E. Use of Open Marsh Water Management Ponds by Ducks, Wading Birds, and Shorebirds During Late Summer and Fall. Frostburg, Maryland: Frostburg State University; 1989.

Site Description

State: Virginia

County: Accomack

Ownership: State

Impoundments

10 impoundments: 381 total acres

Ecology and Management

The impoundments at Doe Creek WMA provide habitat to many waterfowl, shorebirds, saltmarsh birds, wading birds, and provides breeding and wintering habitat to many species as well. This area also provides habitat for a range of invertebrates, fish, amphibians and reptiles, and mammals. The habitats that exist within the complex face a range of natural threats, including an ongoing invasion of Phragmites. The impoundments were constructed primarily for waterfowl management, which is still the primary management focus today. Waterfowl are managed through moist soil management.

Vulnerability

No erosion, over-topping, or storm damage has been documented to date. However, based on its location on the Eastern Shore, there could be some potential for future impacts.

Human Value

The WMA and its impoundments are located on the Eastern Shore in a relatively rural area. The area is primarily used for hunting and not educational purposes. No data exist on the number of visitors.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Steve Living, Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, for providing helpful information used on this page.

Literature Resources

Below is a list of articles describing research occurring at or near the impoundments:

None available

Site Description

State: Maryland

County: Worcester

Ownership: State

Impoundments

EAV 1: 2 acres

EAV 2: 15 acres

EAV 3: 17 acres

Ecology and Management

There are a number of smaller impoundments at E.A. Vaughn WMA, with the largest being approximately 17 acres. The site is used by fair numbers of waterfowl and wading birds. No impoundment-specific data are available for the site, but eBird shows that 222 species have been identified at E.A. Vaughn WMA. Notable findings include an observation of 120 Swamp Sparrows. The upland impoundments at E.A. Vaughn are managed as moist soils while the lower areas generally hold some water year-round.

Vulnerability

E.A. Vaughn WMA borders Chincoteague Bay to the east and the lower areas of the impoundment are vulnerable to sea-level rise and storm surge.

Human Value

There is no human use data available for this site.

Literature Resources

Below is a list of articles describing research occurring at or near the impoundments:

MDNR [Maryland Department of Natural Resources]. E. A. Vaughn WMA. http://dnr.maryland.gov/wildlife/publiclands/eastern/eavaughn.asp 2015:1.

USFWS [United States Fish and Wildlife Service]. Division of Bird Habitat Conservation 2006 Small Grants. Washington, D. C.: United States Fish and Wildlife Service; 2010.

Site Description

State: Maryland

County: Kent

Ownership: Federal

Impoundments

Headquarters Pond: 16 acres

Shipyard Creek: 5 acres

Ecology and Management

Eastern Neck National Wildlife Refuge contains two smaller impoundments. Eastern Neck NWR is the northernmost refuge in the larger Chesapeake Marshlands National Wildlife Complex, which stretches along the eastern shore of Maryland and Virginia. USFWS has identified 240 species of bird at the refuge. The impoundments are regularly surveyed by refuge staff and volunteers. These counts also include croplands on the refuge and adjacent tidal waters, but show robust populations of waterfowl from October – March with a high count of over 45,0000 Scaup (spp.) in the winter of 2004-2005.

There are three impounded moist soil units located on the refuge, only two of which are actively managed. The two managed moist soil units are the 16 acre Headquarters Pond and the 5 acre Ship Yard Creek. The Headquarters Pond unit was created prior to 1967 and Ship Yard Creek was constructed in 2007. Both units are allowed to fill in winter and then drawn down in spring and summer to promote freshwater wetland plant growth.

Vulnerability

Both of the impoundments at Eastern Neck NWR are located upland in relation to the tidal marshes and are therefore relatively protected from the impacts of sea-level rise and coastal storms.

Human Value

Easter Neck NWR receives over 70,000 visitors annually, most of whom participate in wildlife viewing. The refuge has partnered with many local and national outdoor recreation organizations as well as both the University of Maryland and University of Delaware.

Literature Resources

Below is a list of articles describing research occurring at or near the impoundments:

Baird, S. Eastern Neck National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan. Washington, D. C.: U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service; 2010.

Earnst, S. L., and J. Bart. 2013. Costs and benefits of extended parental care in Tundra Swans Cygnus columbianus columbianus. Wildfowl Suplement 1:260-267.

IWMM [Integrated Waterbird Management and Monitoring Project]. Project Update – October 2010. http://iwmmprogram.ning.com/: Integrated Waterbird Management and Monitoring Project; 2010.

Staines, C. L., and S. L. Staines. 2011. The Carabidae (Insecta: Coleoptera) of Eastern Neck National Wildlife Refuge, Maryland. Banisteria 38:71-84.

Staines, C. L., and S. L. Staines. 2005. The Dytiscidae and Hydrophilidae (Insecta: Coleoptera) of Eastern Neck National Wildlife Refuge, Maryland. Maryland Naturalist 47:14-20.

Site Description

State: New Jersey

County: Ocean

Ownership: Federal

Impoundments

Barnegat #1: 18.9 acres

Barnegat #2: 7.06 acres

Barnegat #3: 8.11 acres

Barnegat #4: 82.06 acres

Barnegat #5: 109.79 acres

Ecology and Management

Great egret landing at Edwin B. Forsythe NWR. Photo credit: Rosie Walunas/USFWS.

The Barnegat impoundments are in the central section of the Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge along Barnegat Bay in Ocean County, New Jersey. They are less visited than the extremely popular Wildlife Drive impoundments to the south (also in Forsythe NWR), but they are popular birding spots nonetheless. For example, Barnes (2009) reports 3,800 Greater Scaup, 230 Northern Shovelers, and 200 Northern Pintail using the impoundments during spring migration. Shorebirds and herons are also plentiful where mudflats and shallow waters occur. The site is included in both the International Shorebird Survey (ISS; Chan and Schulte 2008) and the Integrated Waterbird Management and Monitoring (IWMM) programs. Forsythe NWR as a whole is designated a Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network site due to its abundant wetlands and location along the Atlantic Flyway.

The impoundments were originally created as a joint effort of state wildlife and county mosquito control agencies in the late 1960s, and were later acquired by the US Fish and Wildlife Service as part of Forsythe NWR. Due to their distance from headquarters and structural problems associated with their construction, water levels have not been actively managed at this site for some time. Some efforts were made in the 2000s to rehabilitate them in partnership with Ducks Unlimited. However, due to further storm damage, at least two of the five are breached and open to tidal flow, and the other three currently have non-functional water control structures. Forsythe recently performed an engineering assessment of all dams on the refuge including the Barnegat dikes. This, along with a habitat value assessment, resulted in the current plan to transition them from freshwater impoundments back to unmanaged, tidal ecosystems.

Vulnerability

Frequent overtopping and structural instability make the Barnegat impoundments extremely vulnerable to sea level rise and storms.

Human Value

The number of visitors to the Barnegat area of Forsythe NWR is unknown, but the refuge as a whole receives well over 250,000 visitors per year. The Barnegat impoundments are a popular birding spot, and are designated an Important Bird Area due to the abundance and diversity of coastal birds using the site. Approximately 3.9 million people live within 100 kilometers of Edwin B. Forsythe NWR.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Paul M. Castelli and Virginia Rettig (Forsythe NWR) and Joseph Schmidt (Ocean County Mosquito Extermination Commission) for providing helpful information used on this page.

Literature Resources

Below is a list of articles describing research occurring at or near the impoundments:

Atzert, S. P. Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan. Hadley, Massachusetts: U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 5; 2004.

Barnes, S. 2009. Region 3, Waterfowl – Rails. New Jersey Birds 35:103-104.

Castelli, P. Hurricane Sandy resilience projects in New Jersey: Edwin B. Forsythe, Cape May and Supawna Meadows National Wildlife Refuges. Hadley, Massachusetts: Presentation given at the Hurricane Sandy Tidal Marsh Resiliency Coordination Workshop December 8-9, 2014.

Cramer, D. Estimating habitat carrying capacity for American black ducks wintering in southern New Jersey. University of Delaware; 2009.

Ducks Unlimited. Wetland Restoration on New Jersey’s Atlantic Coast. http://www.ducks.org/new-jersey/new-jersey-projects/wetland-restoration-on-new-jerseys-atlantic-coast 2015:1.

Giroux, J., G. Gauthier, G. Costanzo, and A. Reed. 1998. Impact of geese on natural habitats. Pages 32-57 In Batt, B. D. J., editor. The Greater Snow Goose: report of the Arctic Goose Habitat Working Group, US Fish and Wildlife Service and Canadian Wildlife Service, Washington, DC and Ontario, Canada.

IWMM [Integrated Waterbird Management and Monitoring Project]. Project Update – October 2010. http://iwmmprogram.ning.com/: Integrated Waterbird Management and Monitoring Project; 2010.

Kerlinger, P. The economic impact of ecotourism on the Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge area, New Jersey, 1993-1994. Unpublished Report; 1995.

WHSRN [Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network]. 2009. Edwin B. Forsythe NWR. http://www.whsrn.org/site-profile/edwin-b-forsythe-nwr Accessed 2015:1.

Site Description

State: New Jersey

County: Ocean

Ownership: Federal

Impoundments

Stouts Creek East: 45 acres

Stouts Creek North: 16.67 acres

Stouts Creek West: 64 acres

Wrangle Creek East: 7.29 acres

Wrangle Creek West: 10.3 acres

Ecology and Management

Stouts and Wrangle Creeks are two groups of impoundments located within Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge along Barnegat Bay in Ocean County, New Jersey. The Wrangle Creek impoundments were constructed in the 1940s by the State of New Jersey for waterfowl management. One of the Stouts Creek impoundments was created in the 1950s by a waterfowl hunting club, while the other was added in 1972 by state and local agencies for both mosquito control and waterfowl. Both sites are currently owned by Forsythe NWR and are not open to the public. Stouts Creek West is currently breached and all four have non-functional water control structures. Forsythe NWR recently evaluated the structural soundness of these impoundments and found that the high costs of operation and maintenance, along with a habitat value assessment, justify restoring them to open, tidal salt marsh systems.

Vulnerability

These impoundments have low dikes (~2 feet above mean high water) and are therefore subject to overtopping and erosion. Forsythe NWR will be transitioning both sites from freshwater to tidal, non-managed systems in the near future.

Human Value

Stouts and Wrangle Creek are located in an isolated area of Forsythe NWR (boat-access only) and are not open to the public. The broader refuge receives over 250,000 visitors per year and is within 100 km of nearly 4 million people (whsrn.org).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Paul M. Castelli and Virginia Rettig (Forsythe NWR) and Joseph Schmidt (Ocean County Mosquito Extermination Commission) for providing helpful information used on this page.

Literature Resources

Below is a list of articles describing research occurring at or near the impoundments:

Atzert, S. P. Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan. Hadley, Massachusetts: U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 5; 2004.

WHSRN [Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network]. 2009. Edwin B. Forsythe NWR. http://www.whsrn.org/site-profile/edwin-b-forsythe-nwr Accessed 2015:1.

Site Description

State: New Jersey

County: Ocean

Ownership: Federal

Impoundments

East Pool: 549.32 acres

Northwest Pool: 526.58 acres

Southwest Pool: 296.56 acres

Ecology and Management

Black ducks at the Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge, NJ. Photo: Henry McLin (2011) USFWS FLICKR.

The Wildlife Drive impoundments of Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge are renowned for their abundance and diversity of waterfowl, shorebirds, and other water birds. Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge has been designated a Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network site based on the criterion of hosting over 20,000 shorebirds annually. Within the impoundments, 239 bird species have been reported to eBird.org, including impressive high counts of shorebirds and waterfowl. For example, highs of 8,300 Dunlin and 7,600 Semipalmated Sandpiper were reported in East Pool; 8,200 Northern Pintail in Southwest Pool; and 9,500 American Black Duck in Northwest Pool (as of April 2016). Migratory and wintering birds in the impoundments are also monitored by refuge staff and volunteers as part of the national Integrated Waterbird Management and Monitoring program and the International Shorebird Survey (Chan and Shulte 2008).

The impoundments are fed by Doughty Creek and Lily Lake, which allow the Northwest and Southwest Pools to be managed as freshwater. East Pool has been converted to a salt water management regime with water levels managed via tide gates. West Pool is generally drawn down during shorebird migration, which also stimulates the growth of seed-bearing annual moist soil plants. The West Pool is gradually re-flooded during the fall, which results in expanded foraging areas for dabbling ducks and wading birds. The water levels of East Pool fluctuate with the tides but on a delay so that during high tide on the surrounding marsh the impoundment mudflats are exposed and vice versa. The proliferation of Common Reed (Phragmites australis) has been an ongoing challenge (Sun et al. 2007), but has lessened in West Pool due to targeted control and in the East Pool due to the transition to a salt water management regime.

Vulnerability

The Wildlife Drive impoundments at Forsythe NWR are partially sheltered by salt marsh and a barrier island but are nevertheless vulnerable to sea level rise and extreme weather events. The top of the embankments stand at approximately 5 feet above the mean high tide level and have experienced storm damage and erosion over the years. They suffered severe damage during 2012’s Hurricane Sandy when embankments were breached in several places, requiring extensive and costly repairs.

Human Value

The area of Forsythe NWR around the impoundments receives an estimated 120,000 visitors per year, most drawn by the abundance and easy viewing of birds. A dirt road (“Wildlife Drive”) surrounding the impoundments is one of the most popular birding destinations in the state (Applegate and Clark 1987, Kerlinger 1995). Approximately 3.9 million people live within 100 kilometers of Edwin B. Forsythe NWR.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Paul M. Castelli and Virginia Rettig (Forsythe NWR) for providing helpful information used on this page.

Literature Resources

Below is a list of articles describing research occurring at or near the impoundment:

ALS [American Litoral Society]. Assessing the impacts of Hurricane Sandy on coastal habitats. Highlands, New Jersey: American Littoral Society; 2012.

Applegate, J. E., and K. E. Clark. 1987. Satisfaction levels of birdwatchers: An observation on the consumptive—nonconsumptive continuum. Leisure Sciences: An Interdisciplinary Journal 9:129-134.

Atzert, S. P. Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan. Hadley, Massachusetts: U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 5; 2004.

Brown, A., and H. Sun. First Year (Winter 2000) Evaluation of Different Treatments for Controlling Phragmites in the East Pool. Lawrenceville, New Jersey: Rider University; 2000.

Brown, A., and H. Sun. Draft report for baseline investigation of managing Phragmites australis in the Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge. Lawrenceville, New Jersey: Rider University; 1999.

Brown, A., H. Sun, and F. Petrino. Second year (2001) post-treatment evaluation for controlling phragmites in the East Pool at EBFNWR, Brigantine, NJ. Lawrenceville, New Jersey: Rider University; 2002.

Castelli, P. Hurricane Sandy resilience projects in New Jersey: Edwin B. Forsythe, Cape May and Supawna Meadows National Wildlife Refuges. Hadley, Massachusetts: Presentation given at the Hurricane Sandy Tidal Marsh Resiliency Coordination Workshop December 8-9, 2014.

Chan, S., and S. Shulte. A Plan for Monitoring Shorebirds During the Non-breeding Season in Bird Monitoring Region New Jersey – BCR 30. Manomet, Massachusetts: Manomet Center for Conservation Science; 2008.

Conroy, M. J., G. R. Costanzo, and D. B. Stotts. 1989. Winter survival of female American black ducks on the Atlantic coast. The Journal of Wildlife Management :99-109.

Conroy, M. J., G. Costanzo, and D. Stotts. Winter movements of American black ducks in relation to natural and impounded wetlands in New Jersey. Waterfowl and wetlands symposium: proceedings of a symposium on waterfowl and wetlands management in the coastal zone of the Atlantic flyway. Dover, Delaware: Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control; 1987. 31 p.

Conroy, M. J., J. R. Goldsberry, J. E. Hines, and D. B. Stotts. 1988. Evaluation of aerial transect surveys for wintering American black ducks. The Journal of Wildlife Management 52:694-703.

Cramer, D. Estimating habitat carrying capacity for American black ducks wintering in southern New Jersey. University of Delaware; 2009.

Ducks Unlimited. Wetland Restoration on New Jersey’s Atlantic Coast. 2015:1.

Erwin, R. M., J. S. Hatfield, M. A. Howe, and S. S. Klugman. 1994. Waterbird use of saltmarsh ponds created for open marsh water management. The Journal of Wildlife Management 58:516-524.

Erwin, R. M., D. K. Dawson, D. B. Stotts, L. S. McAllister, and P. H. Geissler. 1991. Open marsh water management in the mid-Atlantic region: aerial surveys of waterbird use. Wetlands 11:209-228.

Giroux, J., G. Gauthier, G. Costanzo, and A. Reed. 1998. Impact of geese on natural habitats. Pages 32-57 In Batt, B. D. J., editor. The Greater Snow Goose: report of the Arctic Goose Habitat Working Group, US Fish and Wildlife Service and Canadian Wildlife Service, Washington, DC and Ontario, Canada.

Goldstein, M. A Comparison of Sampling Methodologies to Improve Estimates of Available Food for American Black Ducks in New Jersey. University of Delaware; 2012.

Haglan, B., and M. Spratt. Habitat Management Plan Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge. Galloway, New Jersey: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; Date unknown.

IWMM [Integrated Waterbird Management and Monitoring Project]. Project Update – October 2010. Integrated Waterbird Management and Monitoring Project; 2010.

Jones III, O. E., C. K. Williams, and P. M. Castelli. 2014. A 24-Hour Time-Energy Budget for Wintering American Black Ducks (Anas rubripes) and its Comparison to Allometric Estimations. Waterbirds 37:264-273.

Jones, O. Constructing a 24 hour time-energy budget for American black ducks wintering in coastal New Jersey. University of Delaware; 2012.

Kerlinger, P. The economic impact of ecotourism on the Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge area, New Jersey, 1993-1994. Unpublished Report; 1995.

Sun, H., A. Brown, J. Coppen, and P. Steblein. 2007. Response of Phragmites to environmental parameters associated with treatments. Wetlands Ecology and Management 15:63-79.

WHSRN [Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network]. 2009. Edwin B. Forsythe NWR.

Site Description

State: Maryland

County: Somerset

Ownership: State

Impoundments

Fairmount East: 184 acres

Fairmount West: 132 acres

Fairmount North 1: 12 acres

Fairmount North 2: 18 acres

Ecology and Management

Fairmount WMA is managed by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources and located in Somerset County on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. There are two main impoundments at the site; the 184 acre East Impoundment and 130 acre West Impoundment. Two additional impoundments, currently overgrown and unused occur to the north of Fairmount West. There are no official data on the wildlife present at the site, but eBird lists 140 species observed at the East Impoundment and 90 species at the West Impoundment. Notable high counts for the impoundments include over 1,000 Dunlin and nearly 3,000 Green Winged Teal.

The impoundments are managed for the production of submerged aquatic vegetation.

Vulnerability

The dikes at Fairmount WMA are only 2 feet above MHW and are extremely vulnerable to the effects of sea-level rise and coastal storms. There are also problems with muskrat burrows causing small collapses in the dikes.

Human Value

The site is used mostly by hunters as well as some birders and crabbers.

Literature Resources

Below is a list of articles describing research occurring at or near the impoundments:

MDNR [Maryland Department of Natural Resources]. Fairmount WMA. http://www.dnr.state.md.us/wildlife/Publiclands/eastern/fairmount.asp 2015:1.

Site Description

State: New Hampshire

County: Rockingham

Ownership: Federal

Impoundments

Stubbs Pond: 52 acres

Ecology and Management

The Great Bay National Wildlife Refuge has five freshwater impoundments. However four of the five impoundments don’t function as traditional impoundments. Two are created by dams along a freshwater stream to provide drinking water and two are very tiny ponds that are not managed. Stubbs Pond is the only traditional impoundment in the refuge. It was built in 1963 to provide fishing and boating opportunities to military personnel. However now it is primarily managed to support migratory waterfowl.1 Because Stubbs pond is in a restricted area in the refuge, there is very little eBird data available and no IWMM surveys are conducted at the impoundment (older shorebird surveys indicated little to no shorebird use). However, there are winter bird use data (December to April) from 2010 to 2012. Best available data is listed in the Great Bay NWR Comprehensive Conservation Plan (CCP). According to reports by NH Fish & Game, waterfowl concentrations are highest in the fall, when over 500 ducks and geese have been observed feeding in the impoundment. Several uncommon and state-threatened species have also been observed breeding in the impoundment, including least bittern, sora, common gallinule, pied-billed grebe, and king rail.

While Stubbs pond may not host as many birds as impoundments further south along the Atlantic Coast, it does provide important habitat to a wide range of species and it is recognized as a high-priority waterfowl location within the state of New Hampshire.2

[1] https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Great_Bay/what_we_do/finalccp.html

[2] Personal communication with refuge staff. 2015.

Vulnerability

There are no known records of the impoundment being overtopped during a storm. Erosion has occurred in certain areas around the dam, however it is not known if the erosion was due to a storm event or constant processes. According to the CCP, the dam is in “poor” condition, largely because of the erosion. The “poor” the rating indicates that “a potential dam safety deficiency is clearly recognized for normal loading conditions. Corrective actions to resolve the deficiency are recommended.”

Human Value

Approximately 30,000 people visit the refuge each year.3 There are only two trails on the refuge that are open to the public, and neither provides access to Stubbs Pond. Because Great Bay NWR is a non-staffed refuge, facilitated environmental education programming is not offered at this time.

[3] https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Great_Bay/what_we_do/finalccp.html

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Nancy Pau and Bill Peterson (Park River NWR) for providing helpful information used on this page.

Literature Resources

Below is a list of articles describing research occurring at or near the impoundment:

Taylor, G. W., S. F. Marino, and S. B. Kahan. Great Bay National Wildlife Refuge and Karner Blue Butterfly Conservation Easement Comprehensive Conservation Plan. Hadley, Massachusetts: U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Northeast Regional Office; 2012.

Site Description

State: New Jersey

County: Cumberland

Ownership: State

Impoundments

Heislerville Main Pool: 55 acres

Heislerville North Impoundment: 131 acres

Heislerville South Impoundment: 119 acres

Heislerville West: 5 acres

“There may be no better spring shorebirding spot in NJ than at the Heislerville impoundment.”

-(Elia 2009)

Over 400 bird species have been reported from the Heislerville impoundments.

Heislerville Wildlife Management Area is a state-owned refuge along the Delaware Bayshore in rural Cumberland County, New Jersey. Four contiguous impoundments occur there near the mouth of the Maurice River. The Heislerville impoundments are known among birders as a superb site to see large concentrations of shorebirds, especially when area mudflats are covered by high tides. This is a primary reason it is considered a priority site within the Delaware Bayshore Important Bird Area by New Jersey Audubon. The impoundments are also considered a ‘focal area’ among east coast sites monitored as part of the International Shorebird Survey (ISS; Chan and Schulte 2008). Delaware Bay as a whole is considered an area of hemispheric importance in the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network (WHSRN) as it hosts an estimated 500,000 shorebirds annually. The Heislerville impoundments are well birded. Over 400 eBird checklists have been submitted specifically from the impoundments and over 1,700 from Heislerville WMA as a whole. Over 200 species have been reported, including max counts of 8,000 Short-billed Dowitcher and 7,000 Semipalmated Sandpiper. One source indicates that it can serve as an important high-tide roost site for up to 50,000 individual shorebirds, mainly “peeps” (ALS 2012). A long-term research program studying Semipalmated Sandpiper migration at the site is run by scientists at New Jersey Audubon.

The history of the impoundments is unclear, but the three larger units had new water control structures installed in 2004 by Ducks Unlimited and partners (Kessler 2004). The press release states they were “restored through the installation of state-of-the-art water control structures that will allow for maximizing water level management capability. In turn, this will provide optimal feeding and resting opportunities for waterfowl, shorebirds, wading birds, and endangered Bald Eagles during critical times.” Management of the impoundments is performed by New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) staff. Water levels in the main pool are dropped for northbound and southbound shorebird migration and raised again in the fall. Other pools may be kept full to allow fishing and crabbing activities.

Vulnerability

The Heislerville impoundments were “decimated” during Hurricane Sandy in 2012 (ALS 2012). Overtopping from storm surge caused severe erosion and breaches in the dikes, with an estimated repair cost of approximately $100,000 (AFSBSPT 2013). These embankments are not especially high, averaging about 3-4 feet above the mean high water line. Their proximity to the bay make them vulnerable to sea level rise.

Human Value

The impoundments are frequented by birders, photographers, and fishermen. Their embankments may provide some protection to the buildings and businesses that lie directly behind them on Matt’s Landing Road.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dave Golden and Jason Hearson (NJDEP DFW) for providing information used on this page.

Literature Resources

Below is a list of articles describing research occurring at or near the impoundments:

AFSBSPT [Atlantic Flyway Shorebird Business Strategy Planning Team]. Hurricane Sandy Rapid Assessment – Final Report. Manomet, MA: Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences; 2013.

ALS [American Litoral Society]. Assessing the impacts of Hurricane Sandy on coastal habitats. Highlands, New Jersey: American Littoral Society; 2012.

Bauers, S. 2013. Report finds $50M in post-Sandy bird habitat projects needed. Philadelphia Inquirer / Philly.com January 3, 2013:1.

Chan, S., and S. Shulte. A Plan for Monitoring Shorebirds During the Non-breeding Season in Bird Monitoring Region New Jersey – BCR 30. Manomet, Massachusetts: Manomet Center for Conservation Science; 2008.

Elia, V. 2009. Region 5, Waterfowl – Terns. New Jersey Birds 35:109-111.

Kessler, C. Ducks Unlimited and Partners Finish Wetland Restoration Project at Heislerville Wildlife Management Area. http://www.outdoorcentral.com/mc/pr/04/05/20b8.asp: Ducks Unlimited; 2004.

Sutton, C., and J. Dowdell. Wintering raptors and waterfowl on the Maurice River Cumberland County, NJ: A twenty-year summary of observed status and trends, 1987-2007. Millville, NJ: Citizens United to Protect the Maurice River and Its Tributaries; 2009.

Site Description

State: Virginia

County: Surry

Ownership: State

Impoundments

Fishouse Bay: 281 acres

Hog Island Unnamed 1: 57 acres

Hog Island Unnamed 2: 58 acres

Hog Island Unnamed 3: 130 acres

Hog Island Unnamed 4: 35 acres

Hog Island Unnamed 5: 25 acres

Homewood Creek: 287 acres

Ecology and Management

The impoundments at Hog Island WMA provide habitat to many waterfowl, shorebirds, saltmarsh birds, wading birds, and provides breeding and wintering habitat as well. This area also provides habitat for a range of invertebrates, fish, amphibians and reptiles, and mammals. The habitats that exist within the complex face a range of natural threats, including an ongoing invasion of Phragmites, which is treated on an annual/biennial basis. Erosion of outer marshes threatens integrity of the impoundment system, and nutria, Myocastor coypus, present a potential threat to dike and marsh integrity as does muskrat activity. The impoundments were constructed primarily for waterfowl management, which is still the primary management focus today. Waterfowl are managed through moist soil management.

Vulnerability

No over-topping or storm damage has been documented to date. Some erosion has occurred around the water control structures.

Human Value

The WMA and its impoundments are located in a relatively rural / agricultural area. However, there is a nuclear plant nearby. The area is primarily used for hunting and not educational purposes. No data exists on the number of visitors.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Steve Living, Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, for providing helpful information used on this page.

Literature Resources

Below is a list of articles describing research occurring at or near the impoundments:

Dalmas, T. 1993. White ibises at Hog Island Wildlife Management Area. Raven 64:87-87.

Gooch, B. 2000. Enjoying Virginia Outdoors: A Guide to Wildlife Management Areas. University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville.

Hardaway, C. S. The durability of gabions used for marine structures in Virginia. Gloucester Point, Virginia: Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary; 1988.

Hardaway, C. S., G. R. Thomas, and J. Li. Chesapeake Bay shoreline study: headlands breakwaters and pocket beaches for shoreline erosion control. Goucester Point, Virginia: Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary; 1991.

Thomas Jr., J. 2014. Wildlife are hog wild for Surry County area. Virginian-Pilot December 7, 2014:1.

VDGIF [Virginia Division of Game and Inland Fisheries]. Hog Island WMA. http://www.dgif.virginia.gov/wmas/detail.asp?pid=4 2015:1.

Site Description

State: New York

County: Queens

Ownership: Federal

Impoundments

East Pond: 278 acres

West Pond: 86 acres

Ecology and Management

Terns & Sandpipers over East Pond of Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge. Photo © cometoseemerganser/FLICKR

Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge is a unit within Gateway National Recreation Area located in the borough of Queens, New York City (NYC). The bay is located at the southern end of Long Island, on the Atlantic Flyway, and is well known for its concentrations of waterfowl, shorebirds, and long-legged wading birds (Burger et al. 1983, Brown et al. 2001, Tsipoura et al. 2013). The impoundments (“ponds”) at Jamaica Bay are a centerpiece of the refuge and attract high densities of birds (and birders) due to their low salinities and varying water levels, as well as the readily accessible trails. Birdlife in the area has been well documented through numerous studies and monitoring efforts over the years (Burger et al. 1983, Tsipoura et al. 2013), including citizen science shorebird monitoring following the International Shorebird Survey (ISS) protocol. Birders frequent both impoundments: well over a thousand eBird checklists have been submitted each for East Pond and West Pond! Based on these, over 285 species have been sighted using the two ponds. Impressive high counts of waterfowl (15,000 Greater Scaup, 10,000 Brant) and shorebirds (5,900 Semipalmated Sandpiper, 4,400 Short-billed Dowitcher) have been recorded.

The impoundments were originally designed by architect Robert Moses and constructed by the city of New York in 1954 as part of a bird sanctuary. Water levels in the ponds were managed for waterfowl in consultation with the US Fish and Wildlife Service until 1972, when ownership and management transitioned to the National Park Service (NPS). Active management for migratory birds continued and in recent decades this has entailed lowering water levels in spring and late summer to provide mudflats for migratory shorebirds and raising levels in late fall and throughout winter for migratory and wintering waterfowl. Salinity levels in the ponds have historically been low (near fresh) though the events of Hurricane Sandy impacted this as well as efforts to control water levels.

Vulnerability

Both East Pond and West Pond at Jamaica Bay were hit hard by Hurricane Sandy in 2012. For the first time in their histories, both impoundments were overtopped and breached by rising ocean waters. Prior to this event only minor overtopping (East Pond only) and erosion had been noted following severe storms. The breach to East Pond occurred in several locations on its eastern edge which is formed by an embankment supporting the A-Train, a NYC subway line. This was repaired soon after the storm to resume train operations, sheet piling reinforcements were installed, and the impoundment has gradually returned to back to freshwater. West Pond suffered a major breach in its sandy southern embankment which remains open to the tides. A decision to repair the breach to restore freshwater conditions and water level control to the impoundment was made recently following lengthy public debate and a formal environmental assessment (NYCA 2014, NPS 2015). Construction may begin in fall 2016.

Human Value

“West Pond is one of the few places within the greater New York City metropolitan area that visitors can easily access the refuge.”

– NPS (2015)

Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge is a vital link to nature for many urban dwellers in the NYC region. An average of about 550,000 people visit Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge every year, most starting out on trails around West Pond which begin directly behind the main visitor center (NPS 2015). A significant fraction also crosses Great Bay Boulevard to hike or bird the trails surrounding East Pond. Repairing the breach in West Pond was a high priority among many local and regional birders that frequent the site (NYCA 2014). Non-birders including families, hikers, and nature lovers also take advantage of the trails surrounding the impoundments.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Doug Adamo and George Frame (NPS) for providing helpful information contained on this page.

Literature Resources

Below is a list of scholarly articles describing research occurring at or near the impoundments:

AFSBSPT [Atlantic Flyway Shorebird Business Strategy Planning Team]. Hurricane Sandy Rapid Assessment – Final Report. Manomet, MA: Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences; 2013.

ALS [American Litoral Society]. Assessing the impacts of Hurricane Sandy on coastal habitats. Highlands, New Jersey: American Littoral Society; 2012.

Brand, C. J., R. M. Windingstad, L. M. Siegfried, R. M. Duncan, and R. M. Cook. 1988. Avian morbidity and mortality from botulism, aspergillosis, and salmonellosis at Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, New York, USA. Colonial Waterbirds 11:284-292.

Brown, K. M., J. L. Tims, R. M. Erwin, and M. E. Richmond. 2001. Changes in the nesting populations of colonial waterbirds in Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, New York, 1974-1998. Northeastern Naturalist 8:275-292.

Burger, J. 1988. Jamaica Bay studies VIII: an overview of abiotic factors affecting several avian groups. Journal of Coastal Research :193-205.

Burger, J. 1983. Jamaica Bay studies IV: factors affecting distribution of Greater Scaup Aythya marila in a coastal estuary in New York, USA. Ornis Scandinavica :309-316.

Burger, J. 1982. Jamaica Bay studies: I. Environmental determinants of abundance and distribution of Common Terns (Sterna hirundo) and Black Skimmers (Rynchops niger) at an East Coast Estuary. Colonial Waterbirds :148-160.

Burger, J. 1981. Movements of juvenile herring gulls hatched at Jamaica Bay Refuge, New York. Journal of Field Ornithology 52:285-290.

Burger, J., J. R. Trout, W. Wander, and G. S. Ritter. 1984. Jamaica Bay studies VII: Factors affecting the distribution and abundance of ducks in a New York estuary. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 19:673-689.

Burger, J., R. Trout, W. Wander, and G. Ritter. 1983. Jamaica Bay studies: IV. Abiotic factors affecting abundance of brant and Canada geese on an east coast estuary. The Wilson Bulletin :384-403.

Foderaro, L. W. 2014. Environmental Group Proposes Options for Breached Pond at Jamaica Bay in Queens. The New York Times February 10, 2014:A24.

Kriensky, D. Shorebirds and Horseshoe Crabs in Jamaica Bay: 2014 Update. Presentation given at Harbor Herons Working Group Annual Meeting. New York, New York: New York City Audubon; December 11-12, 2014.

Maillacheruvu, K., D. Roy, and J. Tanacredi. 2003. Water quality characterization and mathematical modeling of dissolved oxygen in the East and West Ponds, Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A 38:1939-1958.