By Anna Haggenjos and Alia Bacon

Project Overview

The Cape May Bird Observatory’s Monarch Monitoring Project (MMP) is believed to be the longest-running research program on a migratory insect in the world. It was created in 1990 and has now collected over 30 years of tagging and census data. Our mission is to monitor autumn monarch migration at Cape May and educate the public through various outreach programs. 2025 also marked the first year that the MMP participated as a partner in the Project Monarch Collaboration and implemented BluMorpho tags, made by Cellular Tracking Technologies, to track monarch movement at a scale and precision not possible before. The solar-powered radio tags allow scientists to track transcontinental insect migration using passive receivers through smartphones across the country. This is also the second year that our new point count protocol has been implemented for counting not only monarchs actively migrating through Cape May Point, but all migratory butterfly species, dragonflies, sphinx moths, and some hoverflies. These counts are uploaded to Trektellen.org under the site named “Cape May Bird Observatory – Monarch Monitoring Project,” where members of the public can check in to see what level of migration is being observed day to day. Collectively, between two forms of tagging and tracking monarch migration, discovering new aspects of insect migration and natural history through our point counts, maintaining native plant gardens, and spreading the word on conservation through public programming and festivals, our team brought together a massive effort in the 2025 season and we are extremely grateful for everyone who was involved.

Research

Point Counts:

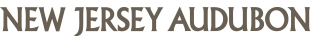

Figure 1. Hourly average Monarch densities recorded during MMP point counts, fall 2025.2025 marked the second year that the MMP conducted stationary point counts. Previously, a driving census was utilized to observe monarch migration through Cape Island. However, issues related to increased tourism and associated road usage, macro- and micro-landscape changes, and general safety concerns all led to the adoption of a new system. Last year, the project switched to stationary point counts from the Coral Avenue dune crossover at Cape May Point. These counts emulate the structure of other CMBO migration counts. The thirty-minute counts are initiated at exactly two, five, and eight hours after sunrise, from September 1 to November 7, and are uploaded to the global migration database Trektellen for public viewing.

Monarchs are primarily counted as they migrate past in two main flight lines: one along the dune line, just south of the count location, and the other along Harvard Ave, just north of the count location. When monarchs are actively moving, they tend to follow these flight lines, flying west or northwest. Any winged insect moving in this direction and observed to be flying with sustained, uninterrupted flight is counted as a migratory insect. If insects are milling about and not displaying migratory behavior, they are not counted. Switching from a census to a stationary point count allows the MMP team to record sixteen species of dragonflies and eighteen additional species of butterflies, in addition to monarchs. Documenting insect diversity during a migratory count is novel, as general insect movement remains largely unstudied. We believe this to be the first effort of its kind anywhere.

Dune Flight line, Photo by Jack McDonough

This fall was both interesting and unusual for migration in Cape May. Throughout the season, monarch movement was notably low. Northeast winds dominated through September and ushered many migrating winged animals inland and away from the coast. Bird and insect movement was significantly diminished compared to previous years due to these unfavorable winds. Monarch migration at Cape May typically peaks during late September and early October. However, that was not the case this year. Peak movement was observed only during an isolated few hours in October. On October 8, over 500 monarchs were counted in 30 minutes during the last count of the day. The next day, the winds shifted to the northeast and the movement dramatically dropped. A lack of consistent northwest winds is most likely the cause for low monarch numbers this year. Monarchs probably traveled more inland away from the coast.

Monarchs were not the only species seen in lower numbers this fall, as several others reflected a similar pattern. Every year, the MMP also counts Cloudless Sulphurs. These large, fast, yellowish-green butterflies are normally seen in large numbers during the first few weeks of September. Over 400 were counted last fall during point counts. This year, only 17 were counted. The exact cause of diminished Cloudless Sulphur numbers is not clear, as they haven’t been heavily studied the way monarchs have. Sulphur densities also do not seem to be impacted by wind direction as directly as monarchs. In previous seasons, Cloudless Sulphur numbers remained high in early September despite sustained northeast winds. A possible explanation is that populations crashed as a result of a harsh winter that did not permit larvae to survive. Red Admiral, another migratory/dispersive butterfly species, was also observed in low numbers this year, with the first not sighted until October 5.

As previously mentioned, wind direction most likely played the largest role in lower migratory insect densities observed during fall 2025. Northwest winds associated with high pressure are typically viewed as the main driving force that ushers migrating birds, insects, and bats toward the coastal plain and into the Cape May peninsula. However, if sustained northwest winds are scarce, many animals will migrate to the west, or inland, of Cape May. According to weather data collected in September, wind direction contained a northwesterly component during just 12% of all counting time. In October, that percentage increased to 20% of all counting time. Even though monarch numbers during fall 2024 were also considered to be relatively low, many more were observed during the point counts than in 2025. In 2024, winds contained a northwesterly component during just 5% of September point counts, but that mark jumped to 30% of October point counts. October 2024 also saw several consecutive-day streaks with northwest winds, essential for drifting monarchs onto the outer coastal plain and causing them to accumulate at Cape May Point.

On a more positive and intriguing note, the MMP’s point counts were crucial in detecting a Red Saddlebags irruption at Cape May during fall 2025. This is a primarily western dragonfly species that is thought to be a vagrant to NJ during the fall only. Typically, only a couple at most are seen each autumn, but in 2025, the MMP recorded 18 during standardized point counts, with several more sightings outside counting hours. A total of 9 were recorded in September, and 9 more were seen in October, suggesting a season-long event. There is relatively little known about the vagrancy patterns of rare dragonflies, making this data important to collect. Patterns for species such as Red Saddlebags and Striped Saddlebags (the latter saw a season total of 11 individuals, with 10 recorded during October) may, in time, become clearer as we continue to collect data on their numbers and annual presence at Cape May.

Tagging:

Conventional tagging of monarch butterflies provides valuable insight into the migration patterns of the last generation of monarchs, frequently known as the “super generation.” By collecting data on these individuals that delay reproducing and instead travel south across North America, we can better understand monarch migration as a whole. At Cape May, this information helps us gain insight regarding how the Eastern monarch population utilizes Cape Island, when significant influxes of monarchs can be expected, the overall condition of Monarchs utilizing the area, and how we can better protect the resources they require along their migration path.

The MMP’s tagging efforts date back to 1992. The MMP exclusively uses a lightweight circular sticker tag developed by MonarchWatch, which is based at the University of Kansas. This tag features a strong adhesive side that is attached to the monarch, following the removal of a small number of scales from the ventral side of the hind wing. Weighing about 10 milligrams, these tags are just 2% of a monarch’s body weight, ensuring that they do not impede the butterfly’s behavior or flight patterns. Each tag contains a unique alphanumeric code, along with a website link for observers to report the tag to MonarchWatch. For every monarch tagged, data is collected on forewing length, wing condition, body fat, sex, time of capture, and location. This data is compiled into our database, providing insight into the physical condition of a small segment of the migrating super generation of monarchs as they travel through Cape May.

In 2025, our Monarch Field Naturalists, MMP Field Coordinator, New Jersey Audubon staff, and dedicated volunteers successfully tagged 1,746 Monarchs. This number reflects a decrease of 1,517 from the total tagged in 2024. This total included 1,181 males and 583 females, indicating that 67% of the tagged population were males while 33% were females.

Radio Transmitters vs Tags

Sticker tags have traditionally served as the main method employed for tagging monarch butterflies at Cape May Point and throughout North America. This approach relies on community scientists who encounter a tagged monarch to document the unique alphanumeric code on the sticker tag and report it to MonarchWatch. Since this method is reliant on human observations, it provides limited insight into the migration behaviors of Monarchs during the fall, only capturing a snapshot of their journey southward.

This year, a secondary tagging method was formally implemented as a part of the MMP’s efforts. Since these tags utilize Bluetooth technology, anyone’s smartphone can act as a receiver to help researchers collect data. BluMorpho-tagged Monarchs can also be detected through the Project Monarch Science app, which is free to download and use on both Apple and Android devices. In addition to real-time tracking, the app also features live maps of migrating Monarchs, with each bearing its own name or code that can be readily searched by app users.

MMP participated in deploying BluMorpho tags, manufactured by Cellular Tracking Technologies, on monarch butterflies; 20 were purchased by the project, while an additional 10 were provided by Cellular Tracking Technologies and the Cape May Point Arts & Science Center through the MMP’s participation as a partner in the Project Monarch Collaboration. The solar-powered radio tags allow scientists to track transcontinental monarch migration using passive receivers through smartphones across the country. Because these tags utilize Blu+ technology, any smartphone with its location services activated can act as a “sensor” to follow of the migratory pathways of individual monarchs. These transmitters are affixed using eyelash glue to the dorsal side of the thorax and transmit data via Bluetooth receivers. While this tagging method takes longer than conventional tagging, given extra time needed for proper application and drying, it offers a significantly greater amount of information regarding the Monarchs’ movements.

Transmitter tagging has significantly enhanced our understanding of monarch butterflies, thanks to the innovative BluMorpho tags created by Cellular Tracking Technologies. This technology delivers real-time insights into migration routes, distances covered, and specific geographical coordinates for each monarch equipped with a solar transmitter.

The information gathered is accessible to the public via an app called “Project Monarch Science,” developed by Cellular Tracking Technologies and the Cape May Point Arts & Science Center. Users can search for tagged Monarchs recently deployed by various project partners, as well as access details about all butterflies outfitted with solar transmitters.

Photo by Caroline Behnke

Photos by Caroline Behnke

BluMorpho Tagging:

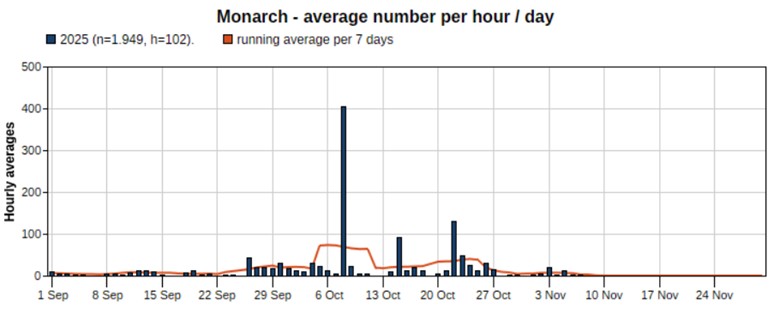

Across North America, approximately 400 radio tags were deployed on monarchs, and the MMP was responsible for 30 of those. Of the monarchs outfitted with BluMorpho tags by the MMP, twelve were subsequently detected outside of New Jersey. Perhaps the most notable of these was an individual dubbed “Fanning,” which was outfitted with a tracking device at Cape May Point on September 26 and subsequently traveled at least as far as central Texas, about 1,300 miles away.

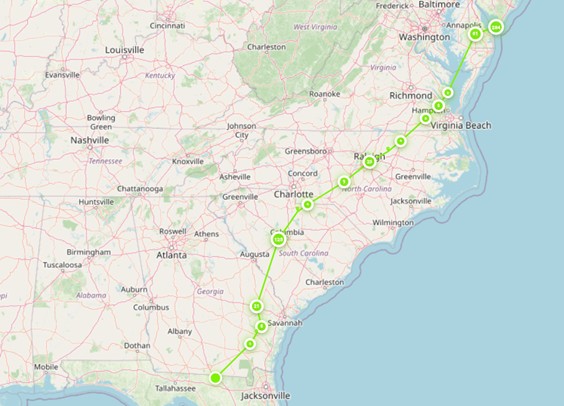

Figure 2. Fanning’s Route (September 26 – October 14)

Fanning crossed the Delaware Bay in just over an hour, launching from the Cape May Point Arts & Science Center and then pinging at the Lewes Ferry Terminal in Delaware. From there, Fanning cut through the middle of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and through the top of Louisiana before ending up between Dallas and Austin, Texas. Staying away from the direct coastline was beneficial for Fanning, as it was able to avoid drifting out to sea or being funneled into Florida.

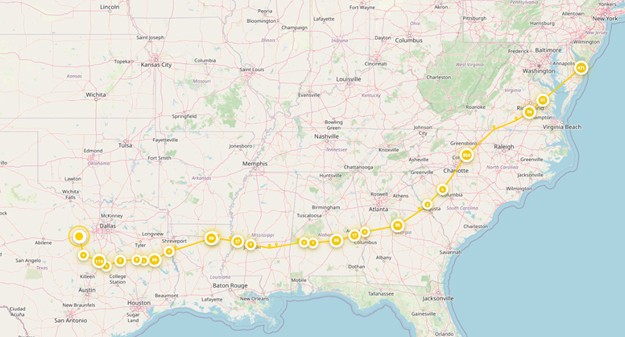

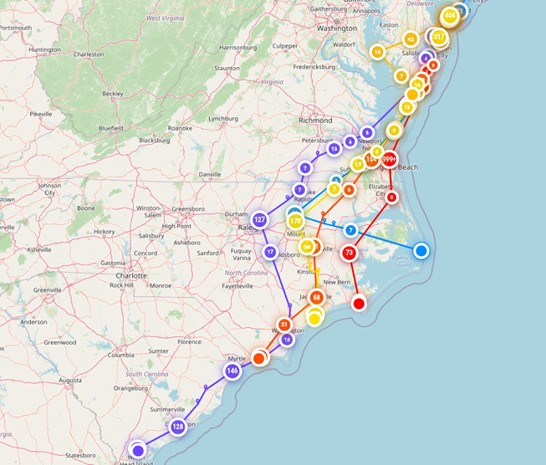

Figure 3. Goodall’s Route (October 4 – October 15)

Another long-distance flyer was named after the late Jane Goodall and tagged October 4. Goodall also crossed Delaware Bay the day after it was tagged, with subsequent detections in Delaware just over two hours later. Goodall then crossed Chesapeake Bay on October 9, again in around two hours. Despite moving incredibly quickly, Goodall stopped pinging about ten days later, with its last detection coming from the panhandle of Florida. It is possible that the monarch was hit with bad weather once reaching Florida. It is impossible to tell if Goodall was going to continue south into the Florida peninsula or move west along the Gulf Coast toward Mexico.

Figure 4. Routes of 6 monarchs tagged at Cape May Point by MMP, all after October 22.

There are many potential applications and new avenues to pursue when considering what we will learn from this new technology. Some Monarchs with BluMorpho tags appeared to take different routes during different parts of the season. Four of the monarchs deployed in late October used the Eastern Shore of Virginia to cut across the Chesapeake Bay over its shortest portions. These monarchs similarly continued down the coast, eventually getting pushed out to the barrier islands of North Carolina. During the first week of November, coastal North Carolina experienced a low-pressure weather system that brought thunderstorms and strong winds. These conditions potentially contributed to similar tracks for all four individuals.

This new technology will allow scientists to understand insect migration better than ever before. Monarchs are naturally not the only species that migrate long distances; some dragonflies may travel farther than monarchs do. This type of tracking technology may have a prominent role in the future of insect migration research, and the MMP is excited to play a part.

Roost Counting:

Fall monarch migration also coincides with decreasing nightly temperatures. Monarch are ectotherms, meaning they cannot regulate their body temperature. Therefore, they cannot fly in temperatures below 55 degrees Fahrenheit. Large migratory movements of monarchs at Cape May usually correspond with the passage of cold fronts. On these cold nights, monarchs display a behavior called roosting, which helps keep them alive in these conditions. They gather on coniferous trees near the dunes, which act as a buffer from wind and cold weather. Clustering close together helps keep the monarchs warmer than if they were all spread out on different trees. This behavior also acts as an anti-predation technique. The more monarchs huddle in one spot, the less likely any one of them is to become prey.

This season, no substantial monarch roosts were observed at Cape May Point. This is highly unusual, as even during years with low monarch numbers, at least some roosting is typically observed. Roosts usually form on nights when peak migration has been observed during the day. In previous years, roosts occurred on days with the highest monarch counts of the season. October 8 saw over 500 monarchs counted during the MMP point counts, and in theory, it would have been an evening when roosts were observed. However, early October was still unusually warm, with the high temperature that day reaching 70 degrees Fahrenheit. Without cold weather, monarchs presumably do not receive environmental cues to roost. It is possible that roosts were not seen this year because of the low number of migrating monarchs, coupled with warmer-than-average temperatures.

Another consideration could be the evolving maritime habitat across Cape May Point’s dune system. Introduced Japanese black pines, which comprise the majority of trees that monarchs roost on during the fall, have slowly been dying in recent years from disease. Over the last two years, many trees have died or are currently dying, which has potentially allowed stronger winds at sites that previously offered dense and secure habitat for roosting monarchs. Native plantings of Eastern Red Cedars or other pine species not affected by the same disease will potentially be necessary to ensure the future of this unique coastal environment that so many migratory species rely on.

Outreach and Education

In-person Engagement:

In addition to long-term monitoring initiatives, the other main goal of the MMP is to educate as many people as possible about monarch migration, conservation strategies, and gardening for wildlife. People are less likely to advocate for the conservation of a species without a strong personal connection. Because of this, a large portion of the MMP season is dedicated to public outreach and education through tagging demonstrations, drop-in programs, and special events.

The first, and most popular, of those is Monarch Tagging Demonstrations. Every Friday, Saturday, and Sunday of the season (weather permitting), the MMP team holds public tagging demonstrations at Cape May Point State Park. These demos typically last an hour, with a 30-45 minute informal presentation on the project’s history, current fieldwork being conducted, monarch biology and life history, and ways that people can help monarchs and other pollinators. Each demo concludes with staff and volunteers divvying up the crowd into smaller groups, walking participants through the conventional tagging process, and then releasing newly tagged butterflies. At these programs, the team provides educational resources about pollinators and native gardening, as well as free milkweed and other native plant seeds (provided by the Diane Cornell Wildlife Garden Project).

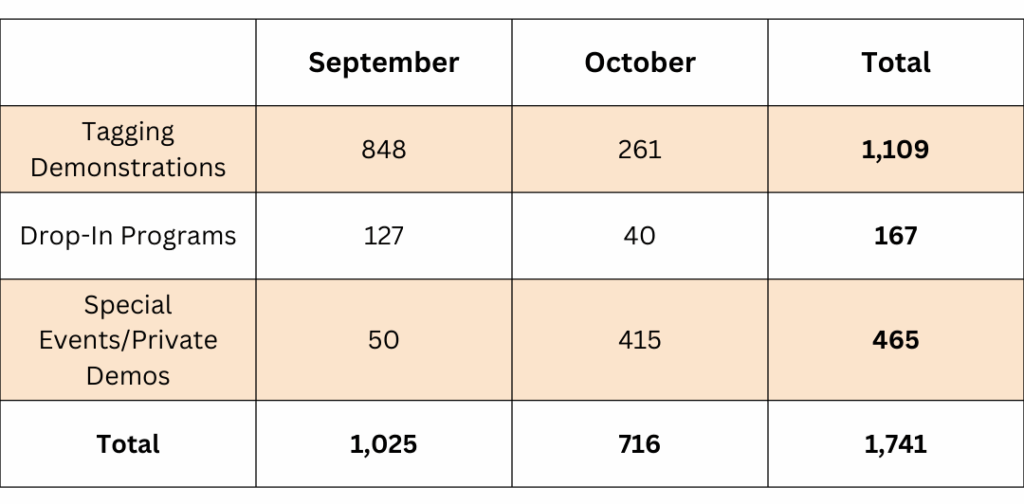

Additionally, MMP holds public drop-in programs at the Nature Center of Cape May, where a monarch rearing station is maintained, twice a week throughout September and October. Across our tagging demonstrations and drop-in programs, we cumulatively reached 751individuals about the importance of conserving monarchs.

The annual Monarch Fest at NJ Audubon’s Nature Center of Cape May was held on September 28, 2025, and attracted over 1,300 visitors; it was the largest festival yet! The MMP held four tagging demonstrations throughout the day, including one with an ASL Interpreter, Emily Krause. Each program was attended by over 100 guests, with over 500 people in total across all tagging demonstrations. The annual Cape May Fall Birding Festival also provided us with a weekend to represent the MMP at Convention Hall. Over the three days of the festival, in excess of 400 people stopped by our table, and about 45 people were present each day at the 12:00 PM tagging demos at Convention Hall. We were also able to welcome an Environmental Science class from Camden High School to Cape May Point State Park for a conventional tagging and BluMorpho deployment demonstration. We were thrilled to share the science and passion behind this project with 12 students and their teacher.

Figure 5. Attendance at MMP programming during fall 2025.

Volunteers:

We are very grateful for the wonderful support from our dedicated volunteers and staff. In total, the Monarch Monitoring Project volunteers contributed 170.5 hours assisting with programming, tagging, and inputting tagging data this fall. We offer sincere thanks to our amazing volunteers: Marg Salvia, Nancy Marckle, Jan Zimmerman, Betty Ross, Wendy Ford, Diane Tassey, Gayley Steffy, Chloe Selover, and Mark Garland. Additionally, we want to say a special thank you to our returning Field Coordinator, Jack McDonough, our returning Monarch Field Naturalist, Anna Haggenjos, and our new Monarch Field Naturalist, Alia Bacon, for all their hard work and support this season.

Thank you all for an incredible 2025 season; the Monarch Monitoring Project is looking forward to another year of continuing our education, research, and conservation efforts!