By Ryan Hasko

The attraction to fire feels innately human, drawing both feelings of appreciation and respect whenever near one. Providing light and warmth, so many of us enjoy the crackling of a hot fire in a fireplace or sitting around a campfire on a cool night. Just as humans have evolved with fire using it as a tool in numerous ways, many of our forested ecosystems have also evolved to adapt to the presence of fire in different manners. Whether its oaks in upland hardwood forests which have developed thick bark to prevent damage during a wildfire or Pitch Pine in the Pinelands whose serotinous cones require fire to release their seeds, forests throughout New Jersey have adapted resiliency to the presence of fire over the course of millennia.

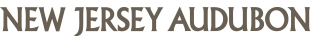

Historic mean fire intervals in the USA

Significant research has examined historical fire regimes throughout Eastern North America, dating fire presence on the landscape to over 17,000 years ago. By examining and carbon dating charcoal fragments in soil cores (known as paleoecology) and looking at cross sections of trees that contain fire scars (dendrochronology) ample evidence has been gathered to estimate the frequency of fires that occurred in forests throughout the northeast. For New Jersey, the Mean Fire Interval (average number of years in between fire occurrences) most likely ranged from 15-20 years in northern NJ and 5-7 years in southern NJ, broadly speaking. Additional information on the science of how these ranges were calculated can be found here. Naturally, fire occurrences fluctuate due to weather patterns, seasonal differences occurring from year to year, and topography of the land. For instance, a drier slope with southern exposure is more likely to experience a fire than a cool, moist, north-facing alcove. Across the landscape however, on a broad scale, fire was a crucial component of ecosystem function in forests throughout New Jersey.

Fast forward to present day, Smokey the Bear is one of the most well-known American icons of the last century, helping to promote the prevention and suppression of wildfires. However, after more than 75 years of successful wildfire suppression, the negative effects of excluding this natural process from forests are being realized. Periodic fires help to reduce and maintain forest fuels from becoming excessive. With aggressive fire suppression, forest fuels accumulate and create significant hazards given certain conditions.

Prescribed burn designed to mimic natural fire siturbance and reduce fuel loads

New Jersey’s pitch pine forests, made up of shortleaf, loblolly, and pitch pine, share similarities with western U.S. forests to that have experienced significant wildfires in recent years. Both are fire disturbance dependent systems, which, if not subjected to frequent low intensity fires, can become dangerous tinder boxes under certain environmental conditions. Thankfully, New Jersey has not experienced recent fires like those in the western U.S., although the risk is real. New Jersey has been receiving more precipitation in recent years, as compared to climate change impacts in the west. We also have a fire surveillance system that is the envy of western firefighters. Circumstances can change quickly however when conditions align to create favorable fire conditions, and even less volatile hardwood forests are undergoing significant changes due to fire suppression, climate change, and forest management decisions. Recognizing that an unmanaged forest is the result of a management decision.

The oak forests of northern NJ also evolved with wildfire. While fires in oak forests did not occur as frequently as in the Pinelands, those fires are equally important to sustaining the oak forest type. Scientists, including foresters, believe that Native Americans had long used fire as a tool to promote conditions favorable for hunting and collecting wild foods and berries. Species like oaks developed adaptations to fire such as thick bark that helped them survive low to moderate wildfires while other thin-barked species like maples and birches were excluded to some degree. Although oak seedlings are more susceptible than mature trees to fire mortality, they have large and well-developed root systems in comparison to the surface roots found on mesic species like beech and maple, and this adaptation allows oak seedlings to quickly resprout after being damaged by fire and repopulate burned areas. These traits allowed oak to sustain itself in forests that otherwise become dominated by the more shade tolerant and moisture preferring maples, birches and beech. With wildfire suppressed for decades, the northeastern US is undergoing a broad conversion of forests from being heavily populated by oak to maple dominance. In fact, red maple has become the most abundant hardwood tree in many northeastern states including New Jersey.

Prescribed burns come in all shapes and sizes, sometimes the fire will mostly just burn the leaf litter, slowly “crawling” forward

What does this shift mean? Oaks support roughly twice as many insects as maples do, which means many migratory birds and other insectivores like bats will have less available food, and the yearly fluctuations in insect populations will have impacts for sustaining local biodiversity. Since oaks are also the cornerstone producers of hard mast in this region, the decline of oaks will mean that numerous birds and mammals that rely on acorns to build reserves to survive the winter will be negatively impacted. With nearly 20 species of oak in New Jersey, it also means that forests will be less diverse and resilient. If oaks are replaced by red maple, beech and black birch forests the risks grow even more significant. The maple, beech, birch forests are generally less suited than oaks to the warmer climate that is expected to become normal for the northeast in the face of a changing climate. This stimulates the question, what could New Jersey forests look like in the future? The answer may be right in front of us as we see many forest patches in highly developed areas overrun with invasive plants and vines, increasingly devoid of mature healthy trees and all the values that come with them. For all these reasons, it is critically important that oak species are sustained as part of our forests.

NJA and NJFFS clearing a fire line

The future does not have to appear so grim though. Although it is not safe to have wildfires in such a human dominated landscape like NJ, New Jersey Audubon is working with the NJ Forest Fire Service and others to increase the use of carefully planned prescribed burning to restore forests, protect people and property, protect critically important carbon stored in mature trees, and to create habitat for wildlife. To do this safely in many places requires the coordinated use of other forestry practices such as thinning. Where the use of prescribed fire is altogether too difficult, other scientifically sound stewardship practices, like shelterwood harvesting, can be used to effectively mimic wildfire and help restore oak forests. When combined with other stewardship activities like invasive species management and deer management, we can change the current trajectory of our forests, to sustain biodiversity, increase resiliency against climate change, and maintain functioning ecosystems that provide clean air and water.