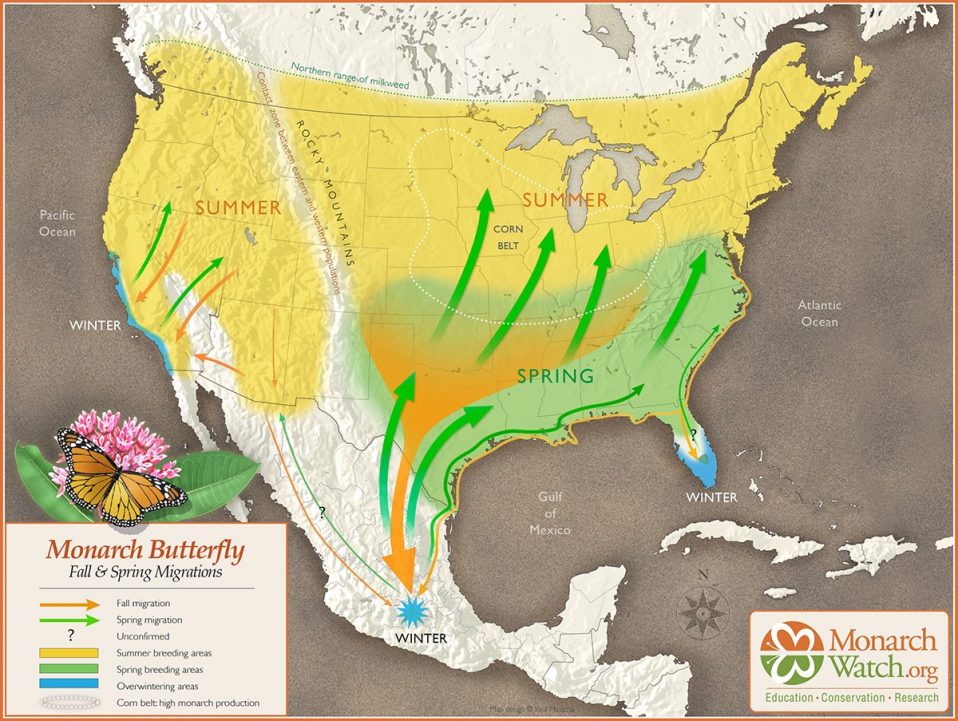

Monarch Migration Map courtesy of Monarch Watch

Director’s Note: Our two seasonal naturalists for 2020, Katherine Culbertson and Jack McDonough, are preparing a series of blog posts designed to educate readers about many aspects of monarch biology and related topics. We will still post updates and summaries on the state of the migration through Cape May, but we hope readers will find these additional posts to be both interesting and informative. The first from this series was written by Katherine Culbertson, titled:

Monarchs are starting to roll through Cape May on their fall migration! While we’re still a ways out from the peak of their migration, monarchs are becoming more commonplace around the Cape, especially in some of the most elaborate native flower gardens. But where did they come from? And where are they going? And why on earth does it matter? Chances are many of you already know the answers to these questions, but to get everyone up to speed, this blog piece – the first in a series of educational blog posts on monarchs – will set out to address these questions.

Monarchs are starting to roll through Cape May on their fall migration! While we’re still a ways out from the peak of their migration, monarchs are becoming more commonplace around the Cape, especially in some of the most elaborate native flower gardens. But where did they come from? And where are they going? And why on earth does it matter? Chances are many of you already know the answers to these questions, but to get everyone up to speed, this blog piece – the first in a series of educational blog posts on monarchs – will set out to address these questions.

The migratory monarchs you are beginning to see now likely hatched out in coastal areas of the U.S. and Canada northeast of Cape May – places including New Brunswick, New England, and the eastern part of New York and Pennsylvania, or perhaps right here in New Jersey. Because the northeast part of North America tapers west as it goes south, many monarchs from the northeast regions travel due south until they reach the coast, and then continue to follow it as it tapers into Cape May, creating a sort of natural funnel for the butterflies. (This is the same reason that Cape May is an incredible birding spot, too!)

Some of the butterflies tagged here in Cape May in the past – at least 90 so far – have made it all the way to Mexico and been recovered there! Our butterflies have been found in several southern states along the flight path to Mexico, too, including Virginia, South Carolina, and Texas. Interestingly, some have ended up in Florida, as well, possibly assimilating into the year-round populations found there. It’s unclear why some monarchs from Cape May end up in Florida, while others make it to Mexico. Did those in Florida end up there intentionally? Or did they simply lose their way on their journey to Mexico, or get detected there en route? Scientists are still trying to figure this out!

Now, the question you’ve all been waiting for: Why is it important to track migrating monarchs? Every monarch enthusiast may have their own unique answers, but I’d contend that tracking monarchs is important for two main reasons: First, monarchs serve as great biological indicator species; second, they are great science education “ambassadors”.

As an indicator species, tracking the health of monarch populations can help us assess the health of the broader ecosystems they depend on. Because monarch populations need a vast expanse of habitat to successfully complete their multigenerational migration, they are one of the first species to suffer from habitat degradation and fragmentation. They are also easy to see and track, unlike many other less visible species dependent on the same habitat. A decline in monarch populations indicates that something is going wrong across the North American landscape, hopefully motivating actions to improve conservation and habitat restoration before many species are adversely affected.

As an indicator species, tracking the health of monarch populations can help us assess the health of the broader ecosystems they depend on. Because monarch populations need a vast expanse of habitat to successfully complete their multigenerational migration, they are one of the first species to suffer from habitat degradation and fragmentation. They are also easy to see and track, unlike many other less visible species dependent on the same habitat. A decline in monarch populations indicates that something is going wrong across the North American landscape, hopefully motivating actions to improve conservation and habitat restoration before many species are adversely affected.