Here in New Jersey we only have one species of hummingbird that breeds in our fair state, the Ruby-throated Hummingbird (Archilochus colubris). But each fall and winter, as many thousands of Ruby-throated hummers have since moved through the state and headed south for warmer wintering locations throughout the southern US, Mexico and Central America, we stand a chance of a visit from a wayward traveller. This is the time of year when a few individuals of other hummingbird species, those which breed in the western United States and Canada, make their way into our region for reasons we don’t completely understand. As part of a long-term winter hummingbird study, I have begun banding these hummingbirds in an attempt to better understand their winter ecology in New Jersey, and to hopefully add a piece to the puzzle being constructed by a collective of hummingbird banders across the country. Where do these birds come from? where do the ultimately go? do they survive through our more temperate winters? and do they continue to take an eastern route in subsequent migrations, rather than the more typical southern path from their breeding grounds throughout western North America? These questions can only really be answered through banding efforts which allow us to measure and weight them to confirm identification as well as assess physiological condition, and resight (or recapture) marked individuals to understand migration pathways as well as assess longevity.

As with most things this is a numbers game, and getting meaningful data typically takes years since we’re talking about a small number of individuals each year. The odds of resighting or recapturing, or having someone else recapture or resight a previously banded bird, are low; but it happens and each time it does it pushes our understanding forward another step. In most cases, though, a bird is banded, allowing us to positively identify it and assess its condition, and then is promptly released. Sometimes a bird will stick around for several days, or even several weeks, before finally moving on to who knows where. So early last Thursday morning I had the privilege of banding a Rufous Hummingbird (Selasphorus rufus) at Nancy Gallagher’s residence in Barnegat, New Jersey.

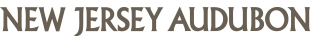

The first image of this new visitor! © Nancy Gallagher

A suite of characters identified the bird as an after-hatch-year (adult) female, including a smooth “adult” bill, free of corrugations which would still be present on a bird born last summer, and a cluster of iridescent gorget feathers concentrated in the center of her throat (since it’s an adult, lacking a full gorget makes it a female by default).

During the banding process. You can actually see how smooth and “groove free” her bill is in this photo, although we always use a hand-lens to confirm the presence or absence of them.

I was able to rule out the similar Allen’s Hummingbird (Selasphorus sasin) based on the width of the outer tail feather, or retrix (they are statistically narrower on Allen’s Hummingbird) as well as wing chord (length) and shape of R2 (the 2nd retrix). She was a lively bird and seemed in very good shape, and returned to the feeder after a brief hiatus following banding. I returned to Cape May and enjoyed a long weekend of jazz during the Exit Zero Jazz Festival, periodically checking up on my hummer host to see whether the Rufous was continuing to visit.

the ‘backside’ shot, showing the very rufous uppertail and mostly green back. © Donna Ortuso

On Monday I had visited two more homes in southern New Jersey and banded a second Rufous Hummingbird, this time a hatch-year female, and a late lingering Ruby-throated Hummingbird (there seem to be a few hanging around late this year). About midday on Monday I received a text from the original homeowner saying that two local birders had spent several hours waiting to see the bird to no avail. It appeared that she had left for good; a bittersweet situation as the homeowner was hopeful the hummer would find her way somewhere warmer to live out the winter. I reminded her that the bird is an adult, and may have done this before in a previous year or years, since we don’t know how old she actually is. later that evening I received an email from someone living in Barnegat Light, right along the Jersey Shore. That morning she noticed a Selasphorus hummingbird coming to her feeder and wanted to know whether I could help identify it. The photos were blurry, but the bird appeared to indeed be a Rufous/Allen’s type, and the clear throat with concentration of gorget feathers in the center of its throat did lean toward adult female.

Could it be her? The initial photos of a “mystery Selasphorus hummingbird” in Barnegat Light on Monday morning… © Pam Fahy

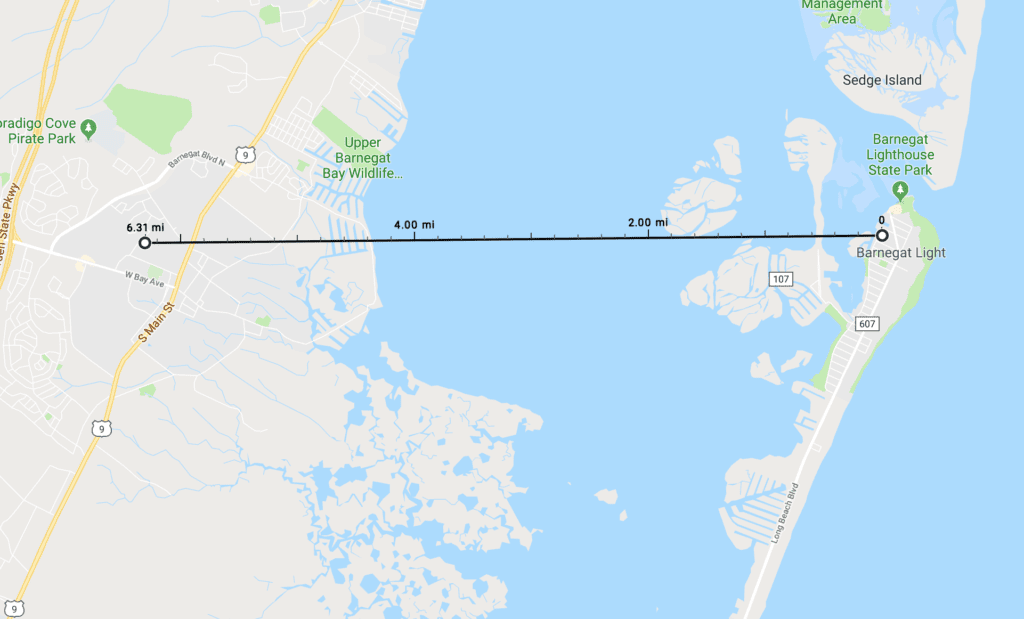

I wondered whether this could be the same bird I had banded five days earlier. I asked the home owner to call me if she was interested in having me come and band the bird, and when we finally spoke she indicated that she thought the bird at her feeder may already be banded! At that point I was ecstatic; even though the two locations are only separated by 6.3 miles, the odds of the same bird being found at a different site are still quite low. If it was her, I didn’t want to recapture her, but I also needed to be sure since it could be a bird that was banded elsewhere, or even from a different year. I needed a conclusive photograph of the band.

I reached out to fellow birder Louis Bizzarro, one of the birders who can camped out unsuccessfully for the Rufous hummer in Barnegat the week before, to see if he would go photograph the band on this bird in Barnegat Light. Louis didn’t miss a beat, and promised to go first thing the next morning. The band on the hummingbird is M 20517 (where M refers to a prefix string which, if printed, would make it too long to fit on a tiny hummingbird band). At 8:00am I received a photo from Louis with a message…

Louis’s confirmation photo showing the last two digits of the band combination “17” ! © Louis Bizzarro

…but I didn’t need to read the message when I saw her band!

“17”

IT’S HER!

Map showing the distance between the two locations. The adult Rufous Hummingbird was first spotted in Barnegat on Monday 11/5 and banded on Thursday 11/8. The bird left Barnegat on Monday 11/11 and was then found visiting the feeder of a residence in Barnegat Light on the same day!

Okay, so I admit, it wasn’t the same as having her resighted in Florida or Alaska, but still – even knowing that she crossed Barnegat Bay and was alive and well tanking up at another feeder was super exciting! Even more so was harnessing the power of social media, a vibrant birding community, and some great camera work from local birders. Where will she go from here? As of today she continues at the home in Barnegat Light. It will be interesting to see whether she sticks through the winter storm we’re currently experiencing. On that note, I checked in with the other homeowner hosting the young Rufous hummer in Burlington County and her bird has made it through the storm, snow and all! It should be no surprise that these hummers are hearty once you consider where they breed. Rufous hummingbirds, in particular, will nest all the way north to British Columbia, Canada, and southern Alaska.

Want to help? If you find your feeders being visited by a hummingbird late into the fall or throughout the winter, and you would like it banded as part of this long-term migration and wintering study, please feel free to contact me via email: [email protected] and leave me a contact number where I can reach you.